Christina Prodinger, Jayne Simpson Allen

Published Dec 02, 2024

15 Strategies to Develop Listening Skills & Speech: Essential Strategy Cards to Use at Home With Children

What is taught and practiced in rehabilitation therapy sessions can provide improved hearing and speaking abilities faster after implantation if these skills are also routinely practiced at home between sessions. This article introduces The Essential Strategy Cards, a free set of cards to assist caretakers and parents as they help young hearing implant recipients develop between therapy sessions.

While rehabilitation therapy sessions lay the groundwork, the most significant progress often occurs at home, where taught strategies need to be consistently applied in everyday situations. To bridge the gap between rehabilitation sessions and home practice, MED-EL Rehabilitation has designed The Essential Strategy Cards. Each card outlines one key strategy to support listening and spoken language development, along with practical examples for incorporating the strategy into daily listening activities.

The cards reinforce essential strategies for caregivers of young hearing implant recipients. In addition, they can help education and health professionals prepare families of pre-implant candidates for the journey ahead. There is a total of 15 cards organized into three key themes:

Getting Ready: How to Prepare a Child for Listening & Create the Best Listening Environment

This category includes four effective strategies for getting a child ready to listen every day.

1. Eyes Open, Ears On

Time spent not wearing hearing devices is lost listening time, and it slows the brain’s process of sorting auditory “noises” into meaning. Ensure that the child’s hearing device(s) are on and working all waking hours. It is important to note that the auditory centers of the brains of children with typical hearing are stimulated 24 hours a day, not only when they are awake.

The more consistently children wear their device(s), the better their language development. If the child removes their device(s), calmly replace it and maintain a positive attitude. The amount of time children spend wearing their hearing device(s) is a strong predictor of their spoken language skills at age three. Additionally, the percentage of listening hours has been found to significantly predict receptive language performance one year after cochlear implantation.Gagnon, E., Eskridge H., Brown, K. & Park, L. (2021). The Impact of Cumulative Cochlear Implant Wear Time on Spoken Language Outcomes at Age 3 Years. Journal of Speech Language Hearing Research. 64(4), 1369-1375. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00567[1]

2. Come Close to Me

Listening with hearing devices is challenging from a distance of more than about 3 meters (10-12 feet), which makes overhearing others’ spoken language difficult or impossible. Stay close to the child so they can hear your words more clearly. This strategy helps to make sure that the auditory signal is clear and your voice stands out from background noise. Since the acoustic characteristics of the learning environment affect the child’s ability to receive clear input, everyone around them should be mindful of the clarity and intelligibility of their speech.Flexer, C. (1999). Facilitating Hearing and Listening in Young Children. Singular Publishing[3]

3. Reduce Background Noise

It is important to be aware of the child’s listening conditions in communication situations. Listening in noise is difficult, especially for people using hearing devices. Noise can disrupt or even mask speech sounds. Make the room as quiet as possible. Your voice should be louder than any background noise.

In addition to staying close to the child’s hearing device, controlling background noise is key in preparing the child to listen so that they have best access to sound. The desired sound signal noise is your voice—every other sound is noise that potentially disrupts the reception and comprehension of speech and spoken language (e.g., TV, other conversations, traffic).Flexer, C. (1999). Facilitating Hearing and Listening in Young Children. Singular Publishing[3] Hence, you should reduce noise sources and add soft furnishing to hard surfaces to absorb sound.

4. Same Thinking Place

Joint attention—when the caregiver and child are focusing on the same object at the same time—is a basis for shared experiences and a necessary aspect of infant development, including the acquisition of language. Notice what the child is looking at or interested in and talk about it—we can assume this is what they are thinking about. By addressing the child’s actions or the objects they look at, you help them associate new vocabulary and syntax with things that are directly engaging and visually meaningful to them.Maclver-Lux, K., Smolen, E., Rosenzweig, E. & Estabrooks, W. (2020). Strategies for Developing Listening, Talking, and Thinking and Auditory-Verbal Therapy. In W. Estabrooks, H. McCaffrey Morrison & K. Maclver-Lux (Eds.), Auditory-Verbal Therapy: Science, Research, and Practice. (pp. 521-561). Plural Publishing.[2]

Listening: How to Promote Active Listening to Develop a Child’s Listening Skills

This category includes six different strategies to promote active listening and develop a child’s listening skills.

5. Acoustic Highlighting

This technique makes a word or sound more evident. Make important sounds or words stand out by saying them with emphasis such as being louder or softer (intensity), longer or shorter (duration), in a higher or lower-pitched voice, or by pausing before the word. Whispering or using a sing-song voice can draw attention to words too.

Always use acoustic highlighting in a natural way to stress a word. This helps facilitate auditory processing, improves auditory perception of speech, and promotes a deeper understanding of language (semantics, morphology, syntax, pragmatics), ultimately supporting spoken language development and cognition.Maclver-Lux, K., Smolen, E., Rosenzweig, E. & Estabrooks, W. (2020). Strategies for Developing Listening, Talking, and Thinking and Auditory-Verbal Therapy. In W. Estabrooks, H. McCaffrey Morrison & K. Maclver-Lux (Eds.), Auditory-Verbal Therapy: Science, Research, and Practice. (pp. 521-561). Plural Publishing.[2]

6. Talk, Talk, Talk

The more parents talk to their children, even in the earliest moments of life, the better their children’s linguistic abilities will be. The variety and complexity of words spoken is as important as the overall number of different words.

Speak about what you and the child see, do, and think to help them learn words and sentence structures as well as how to use them. Speakers talk about what they are doing, seeing, hearing, and thinking (self-talk) and talk about what the child is looking at, doing, most likely listening to, and thinking about (parallel talk).

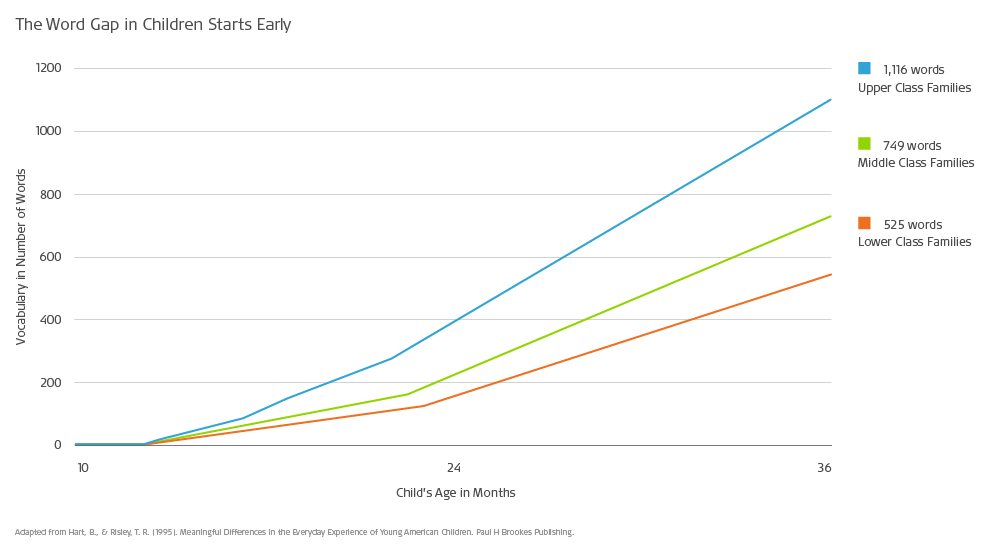

This graph from a study by Hart and Risley illustrates that children who heard more words per hour as babies had larger vocabularies by age three.Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul H Brookes Publishing.[5] The researchers found that socioeconomic status (SES) as well as quantity of words could indicate a child’s vocabulary later on, and you can see in this graph that children with parents who had a higher education learned the most words cumulatively over time.

By 36 months of age, the gap between the number of words heard in these families was about 30 million. On average, the children from the high SES homes heard 2,100 words per hour. These children had larger vocabularies, were better readers, and had higher IQs by the time they started school.

A more recent study showed that both quantity and quality matter in children’s vocabulary development,Rowe, M. L. (2012). A Longitudinal Investigation of the Roles of Quantity and Quality of Child-Directed Speech in Vocabulary Development. Child Development, 83(5), 1762-1774. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3440540/[6] so be more patient when you feel like you’re saying something for the hundredth time and commentating on your toddler’s day—you are seeding their language with more complex vocabulary that will serve them well later on.

7. Wait, Wait, Wait

Pauses and waiting can be helpful in developing turn-taking in conversations as a prompt to entice the child to use their words. After you ask a question or give a direction, give the child time to think and respond. Looking at the child with an expectant look signals to the child that it’s their turn to speak.

Using pauses along with non-verbal cues (e.g., raised eyebrows, a listening posture, or pointing to your ear) can effectively support early spoken communication. Be sure to wait long enough that it feels slightly uncomfortable, and then wait just a bit longer without making it a battle of wills. We are striving for communication, not imitation, with this strategy.Winkelkötter, E. M., & Srinivasan, P. (2012). How can the listening and spoken language professional enhance the child’s chances of talking and communicating during (versus after) the auditory-verbal session? In W. Estabrooks (Ed.), 101 Frequently Asked Questions About Auditory-Verbal Practice (pp. 146-150). Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.[7]

8. Auditory Hooks

Auditory hooks are words or phrases that often have a sing-song feature and seize the child’s attention, prompting them to listen because something exciting may be about to happen. They give a large amount of acoustic information to the child. With words like “Look!,” “Wow!,” “Uh-Oh!,” and “Up, up, up,” you can grab the child’s attention and help make the association between the sound and an object or action. Each time an auditory hook is used, it activates the auditory cortex, directing the child’s focus to spoken language and training the brain to respond through listening.Rhoades, E. A., Estabrooks, W., Lim, S. R., & Maclver-Lux, K. (2016). Strategies for Listening, Talking, and Thinking in Auditory-Verbal Therapy. In W. Estabrooks, K. MacIver-Lux, & E. A. Rhoades (Eds.), Auditory-Verbal Therapy for Young Children With Hearing Loss and Their Families, and the Practitioners Who Guide Them.(pp. 285–326). Plural Publishing[4]

9. Listening First/Auditory Sandwich

Sometimes it is necessary to bridge the gap for children who are struggling to understand spoken information through audition alone. Before you use gestures or visual cues to help your child understand, give them information and instructions with spoken language only. Initially, a child may not have enough auditory access to a speech target to understand how to produce a specific sound.

However, after learning the movement of patterns to successfully create the sound, they may begin associating the available auditory information with the sound’s production. Think of listening as both the starting and finishing points (the bread of the sandwich), with non-auditory cues as the filling. This helps the child develop a solid auditory foundation for producing specific sounds.

10. Say It Again

Caregivers’ speech to young children has features very different to their speech to other adults. An important feature is repetition of their own utterances as well as the child’s utterances. Repetition provides multiple models and several opportunities for a child to practice language. If a child doesn’t respond, it may be because they did not hear fully, did not understand, or missed part of what was said, so repeat what you said or say it again using different words.

Talking: How to Support a Child’s Language Development & Help Them Communicate More

This category includes five different strategies to support a child’s spoken language development and help them communicate more.

11. Auditory Closure

Auditory closure is a cognitive process of filling in missing or unheard pieces of information because we expect it to be there. It involves the speaker pausing during a sentence, song, or story which prompts the listener to fill in the missing word. Start a familiar sentence, song, or rhyme and then stop and wait for the child to recognize and fill in the missing word(s).

This approach stimulates auditory processing, language comprehension, and spoken language and cognitive skills, as it encourages the child’s ability to fill in missing information of a spoken message in order to grasp the whole message.Maclver-Lux, K., Smolen, E., Rosenzweig, E. & Estabrooks, W. (2020). Strategies for Developing Listening, Talking, and Thinking and Auditory-Verbal Therapy. In W. Estabrooks, H. McCaffrey Morrison & K. Maclver-Lux (Eds.), Auditory-Verbal Therapy: Science, Research, and Practice. (pp. 521-561). Plural Publishing.[2]

12. Sabotage

Novel words that are used in unexpected ways can encourage attention and inject some fun into an interaction. Set up situations where your child needs to use words to ask for help or solve a problem by accidentally-on-purpose making a mistake or a mess or saying or doing something the opposite of what was expected.

This engages children in conversations, prompting them to think and speak, as their brains are more responsive to new stimuli than to familiar stimuli. Children learn to use language for problem-solving and come to understand its power, fostering growth in listening, spoken communication, and cognitive abilities.Maclver-Lux, K., Smolen, E., Rosenzweig, E. & Estabrooks, W. (2020). Strategies for Developing Listening, Talking, and Thinking and Auditory-Verbal Therapy. In W. Estabrooks, H. McCaffrey Morrison & K. Maclver-Lux (Eds.), Auditory-Verbal Therapy: Science, Research, and Practice. (pp. 521-561). Plural Publishing.[2]

13. Expansion & Extension

Expansion is the process of repeating what the child says and adding new information such as additional words or corrected grammar. The word order is not changed. This technique is helpful in increasing the child’s length of utterance. Sometimes a caregiver does more than expand the child’s utterance by providing additional information.

This strategy is used to demonstrate and teach the child the next level of language and enrich their vocabulary.Maclver-Lux, K., Smolen, E., Rosenzweig, E. & Estabrooks, W. (2020). Strategies for Developing Listening, Talking, and Thinking and Auditory-Verbal Therapy. In W. Estabrooks, H. McCaffrey Morrison & K. Maclver-Lux (Eds.), Auditory-Verbal Therapy: Science, Research, and Practice. (pp. 521-561). Plural Publishing.[2] If the child says, “red cup,” you can expand by saying, “Yes, the cup is red” and extend by adding, “The red cup is dirty.” An example of extension is responding to the child’s utterance of “red cup” with, “Yes, that is the red cup, and we have lots of colors. This one is yellow.”

14. Use Choices

This is an effective strategy because it gives the child a structured context for communication. It can give them a feeling of control within an interaction and enable them to imitate modeled language. Ask questions with choices so the child can practice making decisions and using spoken language to communicate. You could ask the child, “Do you want the ball or the block?” You thereby allow the child to decide on their own and encourage them to communicate using words.

Practically, you would give the child what they want immediately if they named one option. However, if they point or gaze at one object, you first provide them the If none of the above applies, you wait until the child vocalizes their wish. For children who have more sophisticated language, ask them, “What did you hear?” or “What do you think I said?”

15. My Voice Matters

Communication is two way and this is important to learn. One person speaks and the other person listens, sometimes agreeing or disagreeing, questioning, or adding more information. Language development occurs when the communicative environment is rich and positive. Reinforce a baby’s babbling with positivity. Conversational turn-taking begins before a child produces ”real” words.

Show the child that every sound or word they imitate or say spontaneously is important. This way, you show the child the importance of their voice, encourage their vocalizations, and motivate them to use their voice. This helps the child quickly develop a verbal habit and begin using their voice to communicate naturally.Winkelkötter, E. M., & Srinivasan, P. (2012). How can the listening and spoken language professional enhance the child’s chances of talking and communicating during (versus after) the auditory-verbal session? In W. Estabrooks (Ed.), 101 Frequently Asked Questions About Auditory-Verbal Practice (pp. 146-150). Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.[7] For example, the child might say “wa” for “water.” Praise their attempt. “Oh, you want water!”

The Essential Strategy Cards: A Free Tool to Use at Home With Children

Overall, the Essential Strategy Cards offer caregivers and rehabilitation therapists a practical portfolio of different strategies to support the development of listening and spoken language in children with hearing implants. By incorporating the strategies across the themes of “Getting Ready,” “Listening,” and “Talking” into their everyday activities, caregivers can create an environment that promotes consistent auditory and language growth, thus, empowering caregivers to bridge the gap between therapy sessions and daily life.

Free Tools in Your Inbox

Don't miss the next free download created by our hearing and rehabilitation experts.

Subscribe NowReferences

-

[1]

Gagnon, E., Eskridge H., Brown, K. & Park, L. (2021). The Impact of Cumulative Cochlear Implant Wear Time on Spoken Language Outcomes at Age 3 Years. Journal of Speech Language Hearing Research. 64(4), 1369-1375. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00567

-

[2]

Maclver-Lux, K., Smolen, E., Rosenzweig, E. & Estabrooks, W. (2020). Strategies for Developing Listening, Talking, and Thinking and Auditory-Verbal Therapy. In W. Estabrooks, H. McCaffrey Morrison & K. Maclver-Lux (Eds.), Auditory-Verbal Therapy: Science, Research, and Practice. (pp. 521-561). Plural Publishing.

-

[3]

Flexer, C. (1999). Facilitating Hearing and Listening in Young Children. Singular Publishing

-

[4]

Rhoades, E. A., Estabrooks, W., Lim, S. R., & Maclver-Lux, K. (2016). Strategies for Listening, Talking, and Thinking in Auditory-Verbal Therapy. In W. Estabrooks, K. MacIver-Lux, & E. A. Rhoades (Eds.), Auditory-Verbal Therapy for Young Children With Hearing Loss and Their Families, and the Practitioners Who Guide Them.(pp. 285–326). Plural Publishing

-

[5]

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

-

[6]

Rowe, M. L. (2012). A Longitudinal Investigation of the Roles of Quantity and Quality of Child-Directed Speech in Vocabulary Development. Child Development, 83(5), 1762-1774. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3440540/

-

[7]

Winkelkötter, E. M., & Srinivasan, P. (2012). How can the listening and spoken language professional enhance the child’s chances of talking and communicating during (versus after) the auditory-verbal session? In W. Estabrooks (Ed.), 101 Frequently Asked Questions About Auditory-Verbal Practice (pp. 146-150). Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

-

[8]

Morrison, H. M. (2012). How do children acquire speech without studying mouth and/or face movements in auditory-verbal therapy and education? In W. Estabrooks (Ed.), 101 Frequently Asked Questions About Auditory-Verbal Practice (pp. 184-187). Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

References

Christina Prodinger

Christina Prodinger, BA is an educational scientist currently dedicated to Masters program focusing on adult education and digital literacies. She has been with MED-EL for over a decade, and in her role as a Rehabilitation Assistant, she coordinates adaptations for rehabilitation resources.

Jayne Simpson Allen

Jayne Simpson Allen, Dip T., B Ed., M Ed., C.F., LSLSCert.AVT® commenced work as a Rehabilitation Specialist with MED-EL in 2024. She is the recipient of a Churchill Fellowship, and has worked as an educator, advisor, therapist, and mentor in the field of hearing loss and deafness for over 30 years. Prior to her move to Austria, she lived and worked in Australia and New Zealand, and mentored professionals in Listening and Spoken Language specialization worldwide. She volunteers on the AGBell Academy Board, is a regular presenter at AGBell Symposiums, and collaborated as an author in the book 101 FAQs about Auditory-Verbal Practice.

Was this article helpful?

Thanks for your feedback.

Sign up for newsletter below for more.

Thanks for your feedback.

Please leave your message below.

CTA Form Success Message

Send us a message

Field is required

John Doe

Field is required

name@mail.com

Field is required

What do you think?

The content on this website is for general informational purposes only and should not be taken as medical advice. Please contact your doctor or hearing specialist to learn what type of hearing solution is suitable for your specific needs. Not all products, features, or indications shown are approved in all countries.

Christina Prodinger

Christina Prodinger, BA is an educational scientist currently dedicated to Masters program focusing on adult education and digital literacies. She has been with MED-EL for over a decade, and in her role as a Rehabilitation Assistant, she coordinates adaptations for rehabilitation resources.

Jayne Simpson Allen

Jayne Simpson Allen, Dip T., B Ed., M Ed., C.F., LSLSCert.AVT® commenced work as a Rehabilitation Specialist with MED-EL in 2024. She is the recipient of a Churchill Fellowship, and has worked as an educator, advisor, therapist, and mentor in the field of hearing loss and deafness for over 30 years. Prior to her move to Austria, she lived and worked in Australia and New Zealand, and mentored professionals in Listening and Spoken Language specialization worldwide. She volunteers on the AGBell Academy Board, is a regular presenter at AGBell Symposiums, and collaborated as an author in the book 101 FAQs about Auditory-Verbal Practice.

Christina Prodinger

Christina Prodinger, BA is an educational scientist currently dedicated to Masters program focusing on adult education and digital literacies. She has been with MED-EL for over a decade, and in her role as a Rehabilitation Assistant, she coordinates adaptations for rehabilitation resources.

Jayne Simpson Allen

Jayne Simpson Allen, Dip T., B Ed., M Ed., C.F., LSLSCert.AVT® commenced work as a Rehabilitation Specialist with MED-EL in 2024. She is the recipient of a Churchill Fellowship, and has worked as an educator, advisor, therapist, and mentor in the field of hearing loss and deafness for over 30 years. Prior to her move to Austria, she lived and worked in Australia and New Zealand, and mentored professionals in Listening and Spoken Language specialization worldwide. She volunteers on the AGBell Academy Board, is a regular presenter at AGBell Symposiums, and collaborated as an author in the book 101 FAQs about Auditory-Verbal Practice.

Conversation

2 Comments