MED-EL

Published Jan 20, 2026

Leaders in Innovation: MED-EL Sound Coding for Closest to Natural Hearing

Stimulating the right pitch at the right rate and at the right place in the cochlea enables people with hearing loss to hear with their cochlear implants in a way that comes uniquely close to natural hearing. Simple, right? Not at all. MED-EL’s sophisticated technology that enables closest to natural hearing is anything but simple. Read on to find out what sets us apart from other CI manufacturers and why we are the worldwide leader when it comes to cochlear implant sound quality.

Temporal sound coding and tonotopic electrical stimulation of the entire cochlea are crucial for excellent hearing results with a cochlear implant. MED-EL is able to achieve both with its one-of-a-kind technology.

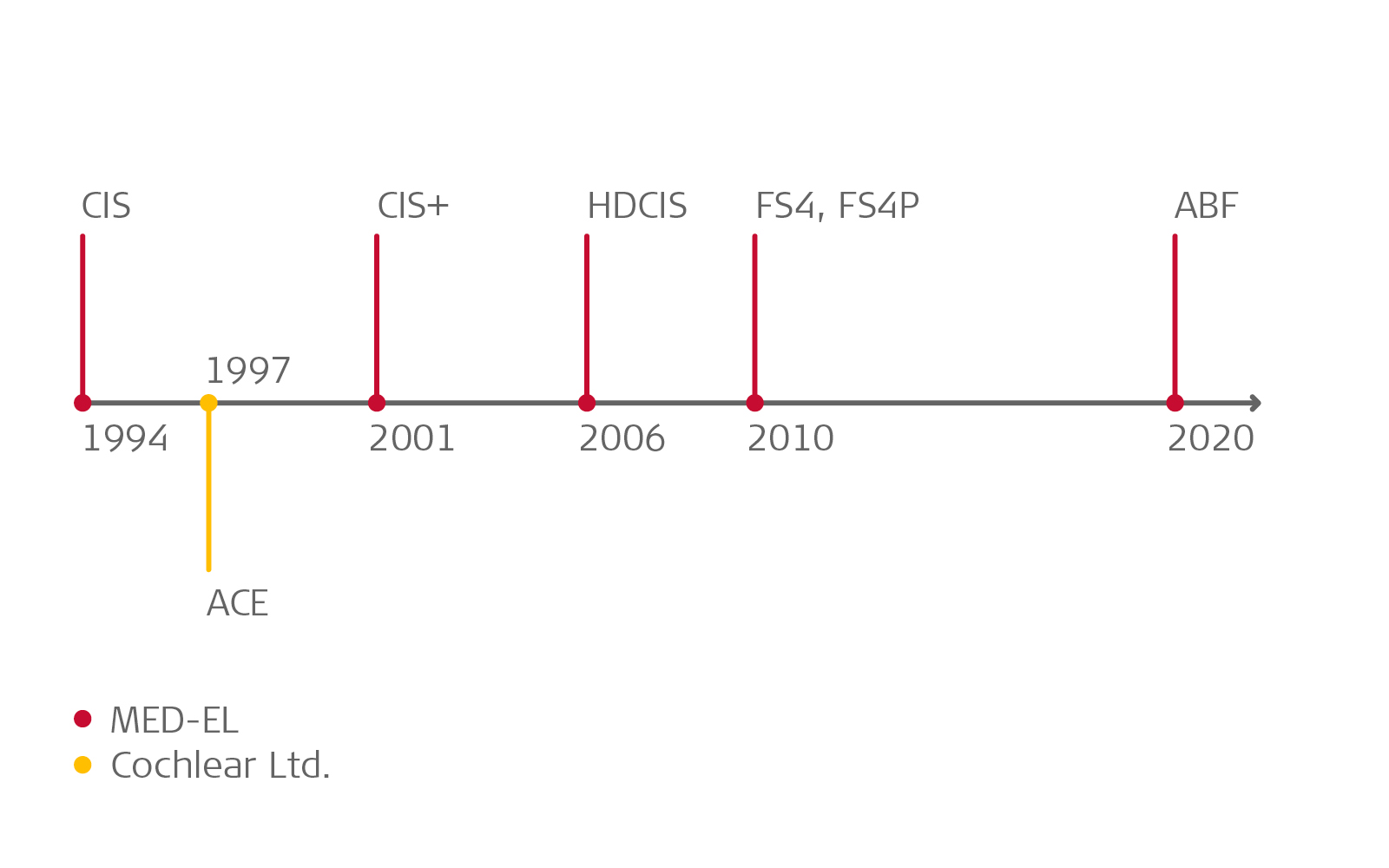

The following graphic clearly shows why MED-EL cochlear implants are able to deliver the closest to natural hearing. While other manufacturers still rely on old sound coding strategies from the 1990s, MED-EL technology has always been—and continues to be—constantly refined to continually increase the quality of hearing for our users.

Predominantly used stimulation paradigms

After the CIS (1994), CIS+ (2001), and HDCIS (2006) coding strategies, FineHearing came in 2010 with FS4, FSP, and FS4-p to take into account the fine structure of sound. Supplementing the FineHearing coding strategy, anatomy-based fitting (ABF) has enabled even more exact tonotopic frequency stimulation in the cochlea since 2020.

Only MED-EL cochlear implants can provide people with hearing loss with individualized cochlear stimulation that matches their unique cochlear anatomy exactly for the closest to natural hearing.

What Is Needed for Closest to Natural Hearing?

- Long, flexible electrode arrays that can be inserted far enough into the cochlea to stimulate all frequencies at their natural place

- A frequency-dependent coding strategy that enables phase-locking—synchronous with the phase of the incoming sound signal—in the second turn of the cochlea, like in natural hearing

- Anatomy-based fitting used for exact tonotopic match

MED-EL cochlear implants meet all of these requirements, making precise frequency perception possible by:

1. Using the entire cochlea.

A cochlear implant can only stimulate the cochlear structures that the electrode array physically reaches. As opposed to other manufacturers’ electrode arrays, MED-EL’s electrode arrays cover the whole cochlea in order to use its full potential and cover the entire range of cochlear frequencies. Thanks to synchrotron imaging, we know that the spiral ganglion extends almost the entire length of the cochlea. The dendrites of the hair cells reach into the second turn of the cochlea. Leaving large parts of the cochlea unstimulated cannot be compensated for by any coding strategy or fitting.

2. Stimulating the right pitch at the right place.

In the cochlea, different hair cells are responsible for different frequencies. Along the basal turn, the higher frequencies are stimulated, and along the apical turn, the lower frequencies. This tonotopic principle is the same for all cochleae, although each one is unique in size and shape.

Tonotopic Stimulation: The Right Place

Comprehensive research shows that better pitch perception with a CI can only be reliably achieved with a match between the natural place of stimulation and the pitch that is stimulated.Dorman, M.F., Cook Natale, S., Baxter, L., Zeitler, D.M., Carlson, M.L., Lorens, A., Skarzynski, H., Peters, J.P.M., Torres, J.H., & Noble, J.H. (2020). Approximations to the voice of a cochlear implant: explorations with single-sided deaf listeners. Trends Hear. 24:2331216520920079.[1]–Harris, R.L., Gibson, W.P. Johnson, M., Brew, J., Bray, M., & Psarros, C. (2011). Intra-individual assessment of speech and music perception in cochlear implant users with contralateral Cochlear and MED-EL systems. Acta Otolaryngol., 131(12), 1270–1278.[18]

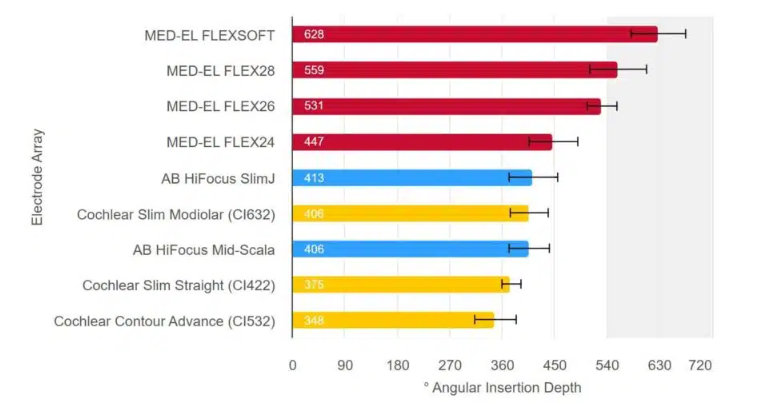

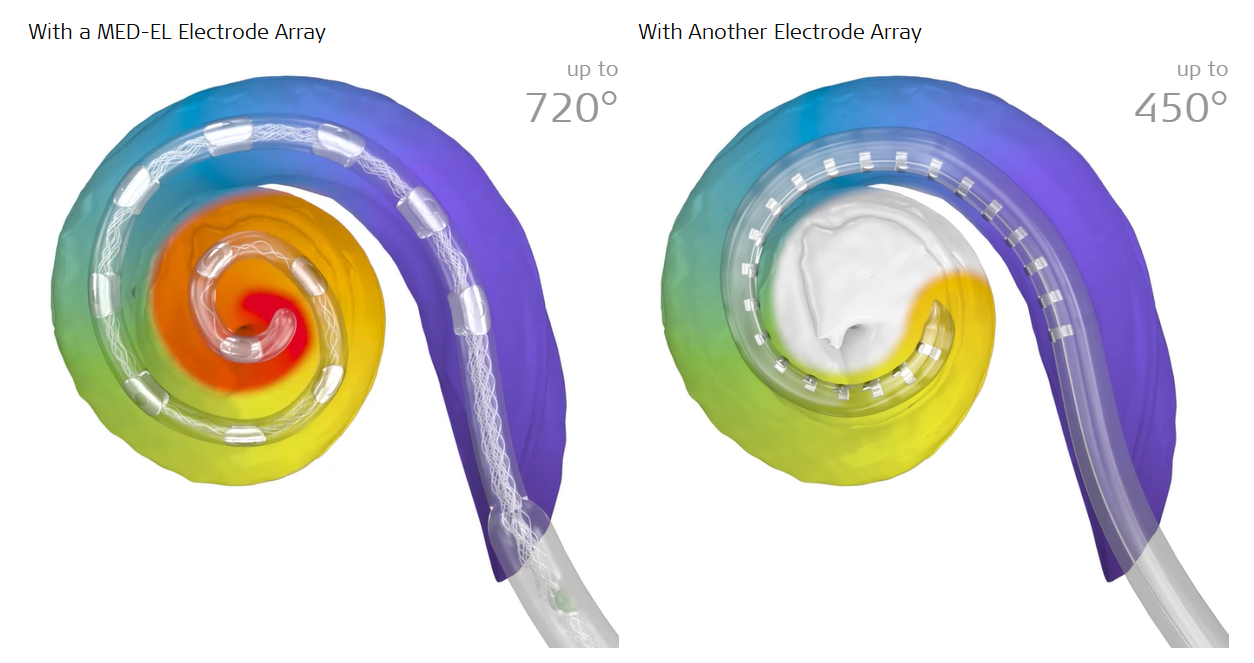

MED-EL’s long, flexible electrode arrays enable safe insertion up to 720°. No other cochlear implant manufacturer can achieve this angular insertion depth and cochlear coverage.Prentiss, S., Staecker, H., & Wolford, B. (2014). Ipsilateral acoustic electric pitch matching: a case study of cochlear implantation in an up-sloping hearing loss with preserved hearing across multiple frequencies. Cochlear Implants Int., 15(3), 161–165.[6]Landsberger, D.M., Svrakic, M., Roland, J.T. Jr., & Svirsky, M. (2015). The relationship between insertion angles, default frequency allocations, and spiral ganglion place pitch in cochlear implants. Ear Hear., 36(5), 207–213.[7] Deep insertions are the basis for using the entire frequency potential of the cochlea, for achieving tonotopic match, and thus for achieving the best possible sound quality.

Sources : Hassepass et al. 2014; Downing 2018; Ketterer et al. 2018; McJunkin et al. 2018; Skarzynski et al. 2018; Weller et al. 2023; Canfarotta et al. 2021.

What effect do short electrode arrays have on sound?

Frequency Compression and Frequency Shift

If an electrode array reaches, for example, only the first 1¼ turns of the cochlea (angular insertion depth: ~450°). A perceptional frequency compression and frequency shift occurs: The lower frequencies will be stimulated at a place that is meant for higher frequencies. That makes sounds like thunder or a dog barking sound significantly higher.

The discrepancy between the natural and the stimulated place in the cochlea increases the lower the pitch, but this also affects higher frequencies, since they are also shifted along the too short electrode array due to frequency compression.

Effect on Sound Quality

Lower-frequency sounds are stimulated and can therefore be heard, but not at their actual pitch—much higher instead. Lower frequencies provide for a rounder, fuller, and more balanced sound. If they are missing, the sound quality suffers greatly: The timbre of sounds, language, and music changes, and sounds lose their fullness, becoming more metallic and unnatural.

If an electrode array is much too short, a tonotopic discrepancy arises that cannot be compensated for—not with neuronal adaptation, not with a sound coding strategy, and not with an audiological fitting.

Natural Rate Coding—The Right Timing

For the most natural sound perception, imitating natural rate coding in the apex of the cochlea is key.

In natural hearing, the processes in the second turn of the cochlea are more complex than in the first turn. Sounds here are not only tonotopically coded but also rate coded. This coding is phase-locked: A 110 Hz sound wave triggers 110 action potentials per second in a nerve fiber, and a tone with a frequency of 263 Hz triggers a chain of 263 action potentials.Dorman, M.F., Cook Natale, S., Baxter, L., Zeitler, D.M., Carlson, M.L., Lorens, A., Skarzynski, H., Peters, J.P.M., Torres, J.H., & Noble, J.H. (2020). Approximations to the voice of a cochlear implant: explorations with single-sided deaf listeners. Trends Hear. 24:2331216520920079.[1]–Prentiss, S., Staecker, H., & Wolford, B. (2014). Ipsilateral acoustic electric pitch matching: a case study of cochlear implantation in an up-sloping hearing loss with preserved hearing across multiple frequencies. Cochlear Implants Int., 15(3), 161–165.[6], Roy, A.T., Carver, C., Jiradejvong, P., & Limb, C.J. (2015). Musical sound quality in cochlear implant users: A comparison in bass frequency perception between Fine Structure Processing and High-Definition Continuous Interleaved Sampling Strategies. Ear Hear., 36(5), 582–590.[12]

That is the reason why just stimulating the correct place is not sufficient in the apical region. If the 120 Hz fundamental frequency of a man’s voice is stimulated at the right place but with a constant rate of 800pps, the nerve cell triggers 800 action potentials per second, which is understood by the brain as pitch shifted upward (in the direction of 800 Hz). You can imagine this like a record player: If the music is played at the normal speed, it sounds natural. If you increase the speed of a song, it not only gets faster but also higher.

For accurate pitch perception, especially for lower tones, an implant must be able to imitate the rate coding of sound waves in the second turn of the cochlea. In other words, the CI has to slow down the pulse rate until it matches the oscillation rate of the corresponding frequency.Schatzer, R., Vermeire, K., Visser, D., Krenmayr, A., Kals, M., Voormolen, M., Van de Heyning, P., & Zierhofer, C. (2014). Electric-acoustic pitch comparisons in single-sided-deaf cochlear implant users: frequency-place functions and rate pitch. Hear Res., 309, 26–35.[3]Prentiss, S., Staecker, H., & Wolford, B. (2014). Ipsilateral acoustic electric pitch matching: a case study of cochlear implantation in an up-sloping hearing loss with preserved hearing across multiple frequencies. Cochlear Implants Int., 15(3), 161–165.[6]

FineHearing Follows Nature

And that’s exactly what FineHearing sound coding from MED-EL does. While the medial and basal channels stimulate at a constant rate, the four apical channels (“fine structure channels”) are able to create phase-locked stimulation. So FineHearing follows the fine structure of sound using synchronous, rate-coded stimulation. A 120 Hz tone is automatically coded with 120 pps, a 144 Hz tone with 144 pps, and so on. Additionally, in bilateral CI users, FineHearing can also code natural interaural time differences, which are important for 3D hearing. Only FineHearing can deliver this powerful combination of closest to natural frequency perception and better localization ability.Roy, A.T., Carver, C., Jiradejvong, P., & Limb, C.J. (2015). Musical sound quality in cochlear implant users: A comparison in bass frequency perception between Fine Structure Processing and High-Definition Continuous Interleaved Sampling Strategies. Ear Hear., 36(5), 582–590.[12]Harris, R.L., Gibson, W.P. Johnson, M., Brew, J., Bray, M., & Psarros, C. (2011). Intra-individual assessment of speech and music perception in cochlear implant users with contralateral Cochlear and MED-EL systems. Acta Otolaryngol., 131(12), 1270–1278.[18]

There are three different FineHearing sound coding strategies: FSP, FS4 with sequential stimulation, and FS4-p with intelligent parallel stimulation. With FSP and FS4, the four apical channels are stimulated consecutively. The parallel FS4-p strategy makes it possible to stimulate two of the four apical channels simultaneously, if necessary. Thanks to the exactly timed stimulation in the apical region of the cochlea, FS4-p ensures that lower frequencies are reproduced truer to nature.

For manufacturers with short electrode arrays that only cover half the cochlea (360-450°), the characteristic rate coding in the second turn of the cochlea is, of course, irrelevant. And the opposite is also true: For manufacturers that do not have the technology to achieve natural rate coding, it would be pointless to use longer electrode arrays. Only by having both long electrode arrays and the right timing can the correct pitch perception for lower frequencies be achieved.

When rate coding that matches frequencies meets the tonotopic coding enabled by long electrode arrays, a cochlear implant can precisely imitate the natural function of the cochlea. The result: closest to natural hearing.Dorman, M.F., Cook Natale, S., Baxter, L., Zeitler, D.M., Carlson, M.L., Lorens, A., Skarzynski, H., Peters, J.P.M., Torres, J.H., & Noble, J.H. (2020). Approximations to the voice of a cochlear implant: explorations with single-sided deaf listeners. Trends Hear. 24:2331216520920079.[1]–Harris, R.L., Gibson, W.P. Johnson, M., Brew, J., Bray, M., & Psarros, C. (2011). Intra-individual assessment of speech and music perception in cochlear implant users with contralateral Cochlear and MED-EL systems. Acta Otolaryngol., 131(12), 1270–1278.[18]

The Impact of Sound Coding on Hearing With a CI

Watch cochlear implant user and neuroscientist Mariia talk with Professor Paul van de Heyning about how MED-EL’s cochlear implant sound simulation compares to how she really hears with her MED-EL cochlear implants.

Anatomy-Based Fitting

Since its introduction with MAESTRO 9.0 in 2020, anatomy-based fitting has been making it possible to match frequency filters with the Greenwood function and thereby with natural cochlear tonotopy. The anatomy-based fitting algorithms in the MAESTRO software focus on the frequency range crucial for speech from 950 Hz to 3000 Hz and match the filter bands to the exact position of the electrode array in the cochlea using postoperative imaging.Dhanasingh, A., & Hochmair, I. (2021). Signal processing & audio processors. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 141(S1), 106–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2021.1888504[19]Mertens, G., Heyning, P. V. de, Vanderveken, O., Topsakal, V., & Rompaey, V. V. (2022). The smaller the frequency-to-place mismatch the better the hearing outcomes in cochlear implant recipients? European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 279(4), 1875–1883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-06899-y[20]

The calculation and assignment of center frequencies according to the position of each individual electrode contact leads to a better tonotopic frequency match and, therefore, to more natural sound perception and to better speech understanding, especially in noise.Mertens, G., Heyning, P. V. de, Vanderveken, O., Topsakal, V., & Rompaey, V. V. (2022). The smaller the frequency-to-place mismatch the better the hearing outcomes in cochlear implant recipients? European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 279(4), 1875–1883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-06899-y[20]Fan, X., Yang, T., Fan, Y. et al. Hearing outcomes following cochlear implantation with anatomic or default frequency mapping in postlingual deafness adults. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 281, 719–729 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-08151-1[21]Kurz A, Herrmann D, Hagen R, Rak K. Using Anatomy-Based Fitting to Reduce Frequency-to-Place Mismatch in Experienced Bilateral Cochlear Implant Users: A Promising Concept. J Pers Med. 2023 Jul 8;13(7):1109. doi: 10.3390/jpm13071109. PMID: 37511722; PMCID: PMC10381201.[22]

Hear the Difference

With our interactive online sound simulator, you can hear how electrode length and anatomy-based fitting affect how a cochlear implant sounds.

Hear the DifferenceInterested in Anatomy-Based Fitting?

Anatomy-based fitting is available in MAESTRO 9.0 or later and is compatible with SONNET 2, SONNET 2 EAS, SONNET 3, SONNET 3 EAS, and RONDO 3. If you would like to learn more about providing your patients with anatomy-based fitting with the help of OTOPLAN and X-rays or CT scans, get in touch with your local MED-EL team.

Subscribe to the Blog and Stay Informed

Subscribe to the MED-EL Professionals Blog and receive exciting posts about new products, the latest research, case studies, and rehab materials direct to your inbox.

This is a translation of the German article written by Max Schnabl, Mag. BA. To read the original German version, change the language option at the top of the page.

References

-

[1]

Dorman, M.F., Cook Natale, S., Baxter, L., Zeitler, D.M., Carlson, M.L., Lorens, A., Skarzynski, H., Peters, J.P.M., Torres, J.H., & Noble, J.H. (2020). Approximations to the voice of a cochlear implant: explorations with single-sided deaf listeners. Trends Hear. 24:2331216520920079.

-

[2]

Dorman, M. F., Natale, S. C., Butts, A. M., Zeitler, D. M. & Carlson, M. L. (2017). The Sound Quality of Cochlear Implants: Studies With Single-sided Deaf Patients. Otology & Neurotology, 38(8), e268–e273.

-

[3]

Schatzer, R., Vermeire, K., Visser, D., Krenmayr, A., Kals, M., Voormolen, M., Van de Heyning, P., & Zierhofer, C. (2014). Electric-acoustic pitch comparisons in single-sided-deaf cochlear implant users: frequency-place functions and rate pitch. Hear Res., 309, 26–35.

-

[4]

Rader, T., Döge, J., Adel, Y., Weissgerber, T., & Baumann, U. (2016). Place dependent stimulation rates improve pitch perception in cochlear implantees with single-sided deafness. Hear Res., 339, 94–103.

-

[5]

Landsberger, D.M., Vermeire, K., Claes, A., Van Rompaey, V., & Van de Heyning, P. (2016). Qualities of single electrode stimulation as a function of rate and place of stimulation with a cochlear implant. Ear Hear., 37(3), 149–159.

-

[6]

Prentiss, S., Staecker, H., & Wolford, B. (2014). Ipsilateral acoustic electric pitch matching: a case study of cochlear implantation in an up-sloping hearing loss with preserved hearing across multiple frequencies. Cochlear Implants Int., 15(3), 161–165.

-

[7]

Landsberger, D.M., Svrakic, M., Roland, J.T. Jr., & Svirsky, M. (2015). The relationship between insertion angles, default frequency allocations, and spiral ganglion place pitch in cochlear implants. Ear Hear., 36(5), 207–213.

-

[8]

Griessner, A., Schatzer, R., Steixner, V., Rajan, G. P., Zierhofer, C., & Távora-Vieira, D. (2021). Temporal Pitch Perception in Cochlear-Implant Users: Channel Independence in Apical Cochlear Regions. Trends in Hearing.

-

[9]

Dorman, M. F., Natale, S. C., Zeitler, D. M., Baxter, L., & Noble, J. H. (2019). Looking for Mickey Mouse™ But Finding a Munchkin: The Perceptual Effects of Frequency Upshifts for Single-Sided Deaf, Cochlear Implant Patients. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR, 62(9), 3493–3499.

-

[10]

Canfarotta, M. W., Dillon, M. T., Buss, E., Pillsbury, H. C., Brown, K. D., & O’Connell, B. P. (2020). Frequency-to-place mismatch: Characterizing variability and the influence on speech perception outcomes in cochlear implant recipients. Ear & Hearing, 41(5), 1349–1361.

-

[11]

Canfarotta, M. W., Dillon, M. T., Buchman, C. A., Buss, E., O’Connell, B. P., Rooth, M. A., King, E. R., Pillsbury, H. C., Adunka, O. F., & Brown, K. D. (2020). Long‐term influence of electrode array length on speech recognition in cochlear implant users. The Laryngoscope, 131(4), 892–897.

-

[12]

Roy, A.T., Carver, C., Jiradejvong, P., & Limb, C.J. (2015). Musical sound quality in cochlear implant users: A comparison in bass frequency perception between Fine Structure Processing and High-Definition Continuous Interleaved Sampling Strategies. Ear Hear., 36(5), 582–590.

-

[13]

Li, H., Schart-Moren, N., Rohani, S., A., Ladak, H., M., Rask-Andersen, A., & Agrawal, S. (2020). Synchrotron Radiation-Based Reconstruction of the Human Spiral Ganglion: Implications for Cochlear Implantation. Ear Hear. 41(1).

-

[14]

Buechner, A., Illg, A., Majdani, O., & Lenarz, T. (2017). Investigation of the effect of cochlear implant electrode length on speech comprehension in quiet and noise compared with the results with users of electro-acoustic-stimulation, a retrospective analysis. PLoS One. 12(5).

-

[15]

Roy, A.T., Penninger, R.T., Pearl, M.S., Wuerfel, W., Jiradejvong, P., Carver, C., Buechner, A., & Limb, C.J. (2016). Deeper cochlear implant electrode insertion angle improves detection of musical sound quality deterioration related to bass frequency removal. Otol Neurotol., 37(2), 146–151.

-

[16]

Dhanasingh, A. & Jolly, C. (2017). An overview of cochlear implant electrode array designs. Hear Res. 356: 93-103.

-

[17]

Timm, M.E., Majdani, O., Weller, T., Windeler, M., Lenarz, T., Buechner, A. & Salcher, R.B. (2018). Patient specific selection of lateral wall cochlear implant electrodes based on anatomical indication ranges. PLoS ONE 13(10).

-

[18]

Harris, R.L., Gibson, W.P. Johnson, M., Brew, J., Bray, M., & Psarros, C. (2011). Intra-individual assessment of speech and music perception in cochlear implant users with contralateral Cochlear and MED-EL systems. Acta Otolaryngol., 131(12), 1270–1278.

-

[19]

Dhanasingh, A., & Hochmair, I. (2021). Signal processing & audio processors. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 141(S1), 106–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2021.1888504

-

[20]

Mertens, G., Heyning, P. V. de, Vanderveken, O., Topsakal, V., & Rompaey, V. V. (2022). The smaller the frequency-to-place mismatch the better the hearing outcomes in cochlear implant recipients? European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 279(4), 1875–1883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-06899-y

-

[21]

Fan, X., Yang, T., Fan, Y. et al. Hearing outcomes following cochlear implantation with anatomic or default frequency mapping in postlingual deafness adults. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 281, 719–729 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-08151-1

-

[22]

Kurz A, Herrmann D, Hagen R, Rak K. Using Anatomy-Based Fitting to Reduce Frequency-to-Place Mismatch in Experienced Bilateral Cochlear Implant Users: A Promising Concept. J Pers Med. 2023 Jul 8;13(7):1109. doi: 10.3390/jpm13071109. PMID: 37511722; PMCID: PMC10381201.

References

MED-EL

Was this article helpful?

Thanks for your feedback.

Sign up for newsletter below for more.

Thanks for your feedback.

Please leave your message below.

CTA Form Success Message

Send us a message

Field is required

John Doe

Field is required

name@mail.com

Field is required

What do you think?

The content on this website is for general informational purposes only and should not be taken as medical advice. Please contact your doctor or hearing specialist to learn what type of hearing solution is suitable for your specific needs. Not all products, features, or indications shown are approved in all countries.

MED-EL

MED-EL