Johanna Boyer, Nathan Schackow

Published Dec 01, 2025

A Guide to Improving Speech Understanding With Meludia Music Training

Cochlear implant technology has rapidly advanced, allowing more recipients to enjoy music—but for some, musical enjoyment does not come easily. This article provides clinicians and speech therapists with an overview of research on the benefits of music training, along with introducing a new rehabilitation and music training resource entitled, Meludia and Speech Understanding: Bridging Exercises.

Aural rehabilitation never starts with listening to an hour-long concerto. Similarly, new runners can’t finish a marathon before they train. Behind each successful marathoner, you’ll typically find a good coach, consistent commitment, and useful objective feedback tools.

Like long-distance runners, recipients of music training with cochlear implants typically benefit the most from shorter training that gradually increases in difficulty over time. Giving up is more likely to occur if their expectations are too high to match their abilities early on.

For runners, coaches and objective feedback tools (like statistics from a sports watch) play a key role in making sure that daily training exercises are realistic based on recent performance. In the same way, Meludia can serve as an objective feedback tool to provide exercises at the right level for aural rehabilitation.

“We have been using Meludia for hearing rehabilitation at our center for three years now, particularly for adults after initial cochlear implantation (CI). The program is an integral part of our standardized hearing training and is individually adapted depending on factors such as age, cognitive and auditory abilities, and the current stage of hearing and language development. Meludia complements our therapeutic work with a structured and motivating approach that specifically promotes fundamental auditory skills in the nonverbal domain—skills that are central to language processing.”

Teresa Schneider

Speech Therapist and Head of Therapy at the LZH in Dornbirn, Austria

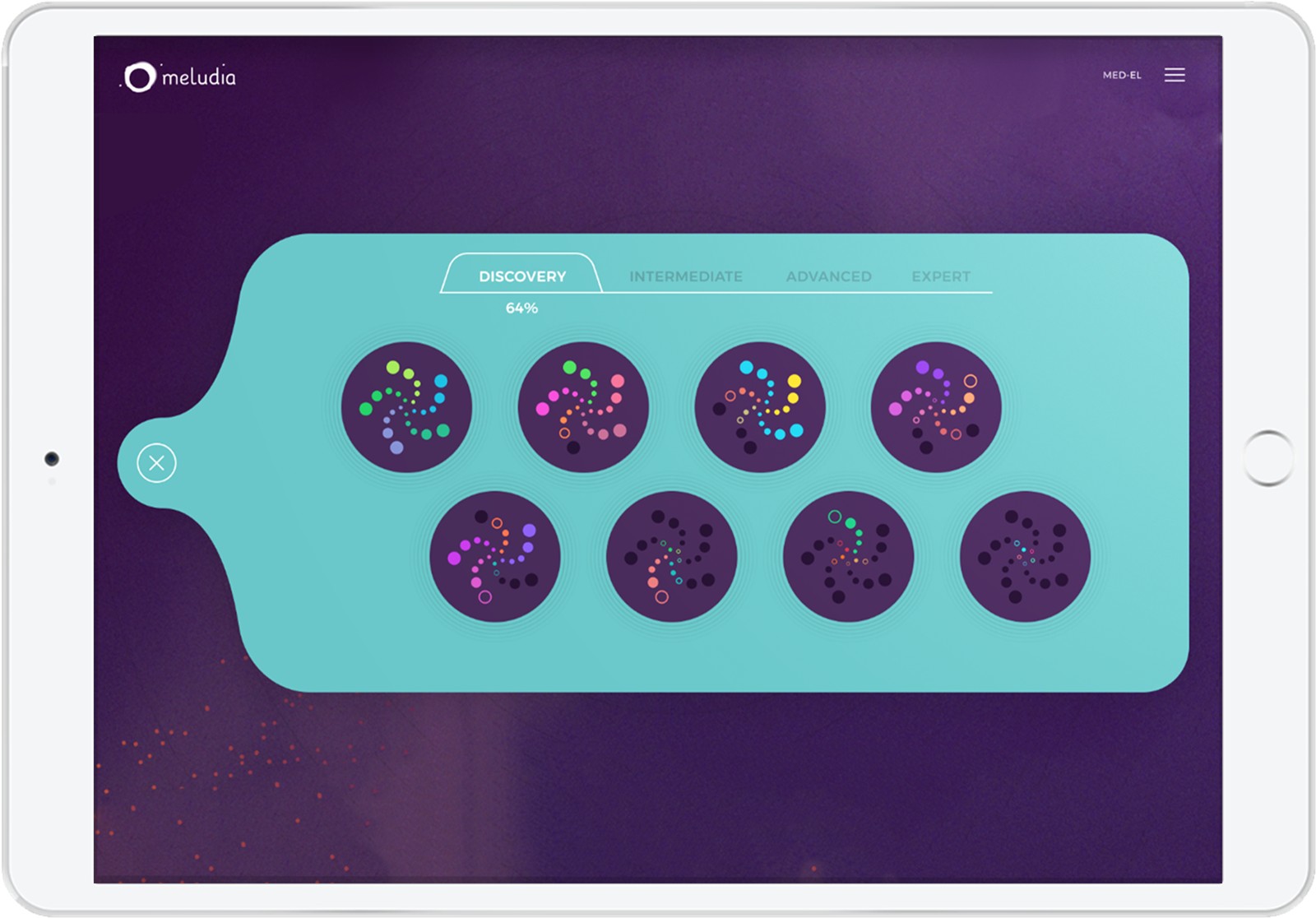

To support cochlear implant recipients on their journey, MED-EL offers free online music training with Meludia on myMED-EL.* With a comprehensive program of over 600 exercises, Meludia can be used by adults and children over the age of 6 on their own and at their own pace. Meludia has four modules (Discovery, Intermediate, Advanced, and Expert) and is currently available in 23 languages.

Can Music Training Strengthen Skills Important for CI Users?

“The bridge between music and language is speech melody. The various prosodic features are present in both music and language. Accent, speech melody, volume, speech rate, rhythm, and timbre are essential parts of language and central components of music. Targeted training in these aspects is particularly important for CI users, who often have difficulty perceiving these features,” said Teresa Schneider.

Music and speech are closely connected. Music influences speech development because there is a close relationship between what we experience when we listen to music and the development of language skills. Research has demonstrated that music training can benefit skills that are of high importance for the cochlear implant population, such as:

- Cognitive abilities Fujioka, T., Ross, B., Kakigi, R., Pantev, C., & Trainor, L. J. (2006). One year of musical training affects development of auditory cortical-evoked fields in young children. Brain, 129(10), 2593–2608. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl247[4]

- Verbal memory Ho, Y.-C., Cheung, M.-C., & Chan, A. S. (2003). Music Training Improves Verbal but Not Visual Memory: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Explorations in Children. Neuropsychology, 17(3), 439–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.17.3.439[5]

- Vocabulary Schlaug, G., NORTON, A., OVERY, K., & WINNER, E. (2005). Effects of Music Training on the Child’s Brain and Cognitive Development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1060(1), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1360.015[10]

- Perception of vocal pitch Moreno, S., Marques, C., Santos, A., Santos, M., Castro, S. L., & Besson, M. (2009). Musical Training Influences Linguistic Abilities in 8-Year-Old Children: More Evidence for Brain Plasticity. Cerebral Cortex, 19(3), 712–723. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn120[8]

- Perception of speech in noisy backgrounds Slater, J., Skoe, E., Strait, D. L., O’Connell, S., Thompson, E., & Kraus, N. (2015). Music training improves speech-in-noise perception: Longitudinal evidence from a community-based music program. Behavioural Brain Research, 291, 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2015.05.026[11]

- Auditory encoding of speech Moreno, S., Marques, C., Santos, A., Santos, M., Castro, S. L., & Besson, M. (2009). Musical Training Influences Linguistic Abilities in 8-Year-Old Children: More Evidence for Brain Plasticity. Cerebral Cortex, 19(3), 712–723. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn120[8]

- Auditory discrimination and attention Kraus, N., Slater, J., Thompson, E. C., Hornickel, J., Strait, D. L., Nicol, T., & White-Schwoch, T. (2014). Music Enrichment Programs Improve the Neural Encoding of Speech in At-Risk Children. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(36), 11913–11918. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1881-14.2014[7]

- Structural changes in auditory cortical areas Kraus, N., Slater, J., Thompson, E. C., Hornickel, J., Strait, D. L., Nicol, T., & White-Schwoch, T. (2014). Music Enrichment Programs Improve the Neural Encoding of Speech in At-Risk Children. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(36), 11913–11918. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1881-14.2014[7]

Music training can benefit listening attention and focus because of stronger auditory discrimination and attention, and improved auditory working memory, Strait, D. L., & Kraus, N. (2011). Can You Hear Me Now? Musical Training Shapes Functional Brain Networks for Selective Auditory Attention and Hearing Speech in Noise. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 113. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00113[13]Torppa, R., Faulkner, A., Huotilainen, M., Järvikivi, J., Lipsanen, J., Laasonen, M., & Vainio, M. (2014). The perception of prosody and associated auditory cues in early-implanted children: The role of auditory working memory and musical activities. International Journal of Audiology, 53(3), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.872302[14] and music training can transfer effects to the speech domain because it enhances verbal memory and comprehensive vocabulary, along with improving perception of vocal pitch and speech understanding in noise. Ho, Y.-C., Cheung, M.-C., & Chan, A. S. (2003). Music Training Improves Verbal but Not Visual Memory: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Explorations in Children. Neuropsychology, 17(3), 439–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.17.3.439[5]Moreno, S., Marques, C., Santos, A., Santos, M., Castro, S. L., & Besson, M. (2009). Musical Training Influences Linguistic Abilities in 8-Year-Old Children: More Evidence for Brain Plasticity. Cerebral Cortex, 19(3), 712–723. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn120[8]Schlaug, G., NORTON, A., OVERY, K., & WINNER, E. (2005). Effects of Music Training on the Child’s Brain and Cognitive Development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1060(1), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1360.015[10]Slater, J., Skoe, E., Strait, D. L., O’Connell, S., Thompson, E., & Kraus, N. (2015). Music training improves speech-in-noise perception: Longitudinal evidence from a community-based music program. Behavioural Brain Research, 291, 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2015.05.026[11]

Pediatric cochlear implant users have also been shown to benefit from music training and musical engagement (such as ear training) and have the potential to achieve performance statistically equivalent to age-matched normal hearing control groups with musical experience. Torppa, R., Faulkner, A., Huotilainen, M., Järvikivi, J., Lipsanen, J., Laasonen, M., & Vainio, M. (2014). The perception of prosody and associated auditory cues in early-implanted children: The role of auditory working memory and musical activities. International Journal of Audiology, 53(3), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.872302[14] When musical training was shown to result in significant improvements on pitch perception exercises with prelingually deafened children, one study surmised that their “modified tonotopy organization … could be further optimized for a more precise resolution of frequency spectrum.” Nardo, W. D., Schinaia, L., Anzivino, R., Corso, E. D., Ciacciarelli, A., & Paludetti, G. (2015). Musical training software for children with cochlear implants. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica: Organo Ufficiale Della Societa Italiana Di Otorinolaringologia e Chirurgia Cervico-Facciale, 35(4), 249–257. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4731893/[9]

Music Training With Cochlear Implants: What Research Reveals

Studies show that cochlear implant recipients can benefit from music training. Specifically, music-related ear training through web-based or software programs has shown great potential. Benefits include enhanced music perception by improving pitch accuracy and timbre perception Jiam, N. T., Deroche, M. L., Jiradejvong, P., & Limb, C. J. (2019). A Randomized Controlled Crossover Study of the Impact of Online Music Training on Pitch and Timbre Perception in Cochlear Implant Users. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 20(3), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-018-00704-0[6]Smith, L., Bartel, L., Joglekar, S., & Chen, J. (2017). Musical Rehabilitation in Adult Cochlear Implant Recipients With a Self-administered Software. Otology & Neurotology, 38(8), e262–e267. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000001447[12] and increased quality of life and musical enjoyment. Frosolini, A., Franz, L., Badin, G., Mancuso, A., Filippis, C. de, & Marioni, G. (2024). Quality of life improvement in Cochlear implant outpatients: a non-randomized clinical trial of an auditory music training program. International Journal of Audiology, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2024.2428421[3]Smith, L., Bartel, L., Joglekar, S., & Chen, J. (2017). Musical Rehabilitation in Adult Cochlear Implant Recipients With a Self-administered Software. Otology & Neurotology, 38(8), e262–e267. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000001447[12]

Smith et al. investigated whether a self-administered computer-based rehabilitative program could improve music appreciation and speech understanding in adults with a CI. 21 adult CI users participated in music rehabilitation training for 4 weeks. Smith, L., Bartel, L., Joglekar, S., & Chen, J. (2017). Musical Rehabilitation in Adult Cochlear Implant Recipients With a Self-administered Software. Otology & Neurotology, 38(8), e262–e267. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000001447[12] The subjects were tested pre-training, immediately after 4 weeks of training, and 6 months post-training. Outcomes indicated significant improvements in musical pattern perception in comparison to pre-training results. Speech perception in quiet and in noise significantly improved in subjects with low musical abilities. Also, music enjoyment improved significantly, and participants thought that the training helped to improve their recognition skills and found the program to be beneficial.

The Research on Music Training With Meludia

Jiam et al. tested 20 adult CI users (with 21 normal hearing individuals in the control group) in a randomized controlled crossover study before and after 4 weeks of music training with Meludia and found that “auditory training (with either acute participation in an online music training program or audiobook listening) may improve performance on untrained tasks of pitch discrimination and timbre identification.” Jiam, N. T., Deroche, M. L., Jiradejvong, P., & Limb, C. J. (2019). A Randomized Controlled Crossover Study of the Impact of Online Music Training on Pitch and Timbre Perception in Cochlear Implant Users. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 20(3), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-018-00704-0[6]

Boyer et al. investigated the suitability of the Meludia for music training with CI recipients. Boyer, J., & Stohl, J. (2022). MELUDIA – Online music training for cochlear implant users. Cochlear Implants International, 23(5), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2022.2069313[1] 38 adult MED-EL CI users completed 14 exercises involving 5 different musical dimensions of the online music training program. The results showed that the easiest exercises available in Meludia are easy enough for CI users to be able to use this training resource independent of age, indication, duration of CI use, or musical background. Another study found that Meludia can be used for music training for CI users of all ages. Calvino, M., Zuazua, A., Sanchez-Cuadrado, I., Gavilán, J., Mancheño, M., Arroyo, H., & Lassaletta, L. (2024). Meludia platform as a tool to evaluate music perception in pediatric and adult cochlear implant users. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 281(2), 629–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-08121-7[2]

Two open-access publications can be viewed for more details on using Meludia for music training with cochlear implant users:

MELUDIA – Online music training for cochlear implant usersBoyer, J., & Stohl, J. (2022). MELUDIA – Online music training for cochlear implant users. Cochlear Implants International, 23(5), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2022.2069313[1]

Meludia platform as a tool to evaluate music perception in pediatric and adult cochlear implant usersCalvino, M., Zuazua, A., Sanchez-Cuadrado, I., Gavilán, J., Mancheño, M., Arroyo, H., & Lassaletta, L. (2024). Meludia platform as a tool to evaluate music perception in pediatric and adult cochlear implant users. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 281(2), 629–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-08121-7[2]

Using Meludia for Music Training to Improve Speech Understanding

“We typically use Meludia with children preschool age (approximately 5 years old) and older. It is appropriate to use it when the child has sufficient skills in terms of attention, responsiveness, and the ability to use simple digital interfaces. The clearly structured visual presentation of the exercises allows for easy access, with the level of difficulty and exercise selection always being individually adapted,” explained Teresa Schneider.

Teresa Schneider has been using Meludia for three years with her team of speech therapists. They have been using Meludia in individual sessions with children (5 years and older) and adults.

She said, “Since integrating Meludia, we have observed improved auditory discrimination skills in many clients, particularly in the areas of pitch perception, rhythmic structuring, and auditory memory span. These improvements are directly reflected in speech therapy contexts, such as more precise sound discrimination (phonemic differentiation), more stable sentence memory, and improved prosody recognition.

“A particularly positive effect is evident in the motivation to practice outside of therapy. Meludia creates a playful, rewarding environment. The level system makes progress directly tangible—many want to “reach another level,” which almost leads to a slight “risk of addiction.” This structure supports independent practice and works even without a practice partner, whether at home on a tablet, on the go on a smartphone, or with aids such as AudioLink or AudioStream.”

While Teresa and her team use Meludia in addition to speech exercises in their speech therapy sessions, they also recommend that their patients use it at home. Teresa noted that Meludia enables clients who don’t have a practice partner or simply prefer to practice on their own to do so.

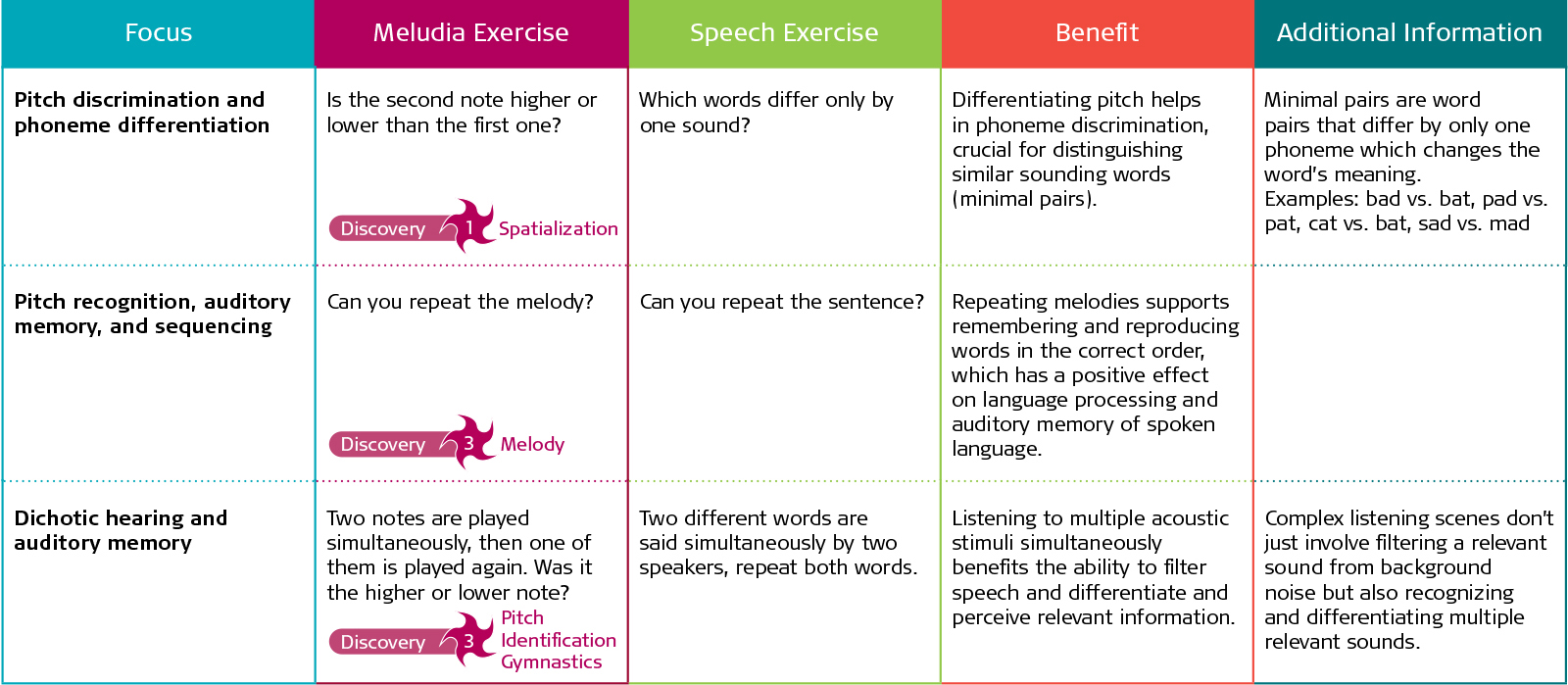

Meludia and Speech Understanding: Bridging Exercises

Teresa Schneider has worked with MED-EL to develop a guide that combines specific Meludia exercises with speech exercises. Based on her experience with Meludia in speech therapy in her center, this guide can help you support cochlear implant recipients in improving speech perception by focusing on one element of music at a time.

Targeted active listening training helps CI recipients train their ears and brains to adapt and learn to interpret pitch, rhythm, and timbre cues. Slow, incremental improvements are typically seen after repeated exposure to and practice with each of the elements of music. Therapists, music training, and Meludia can be game-changing for CI recipients and help manage difficulty levels as well as the focus of each day’s training.

Each Meludia module has eight stars which consist of musical exercises belonging to five different musical dimensions: rhythm, melody, harmony, spatialization, and form. The various exercises develop over 5 levels of increasing difficulty, therefore providing guided and structured step-by-step music training.

Meludia approaches music like learning a language with intuitive vocabulary.

The listener is asked, for example, if a sound example sounded stable or unstable instead of using music terminology like “consonant” and “dissonant.” The goal is to explore the complex sound creations, which are used as building blocks for music. When starting an exercise, sound examples are given to familiarize the listener with different concepts. Gamification, repetition, and visual reinforcement are used to engage and support a successful learning process.

The new resource, Meludia and Speech Understanding: Bridging Exercises, is available on the MED-EL Academy. It was jointly created by Teresa Schneider and MED-EL to demonstrate to professionals how Meludia can benefit speech and be used in aural rehabilitation and speech therapy. This resource includes 11 examples that display specific Meludia exercises that can be used to support speech exercises, with the music exercises functioning as a bridge.

“To realize difficult tasks, try to practice on a non-verbal level and choose the right exercise on Meludia. Then switch back to the related speech exercise.”

Teresa Schneider

The examples in the new resource include Meludia exercises from the first four stars of the Discovery module. But other Meludia exercises can be equally useful and be combined with speech exercises.

The first column of the table sets the focus for the area-related goal and then presents the specific pair of exercises for music and speech. Following that is a description of the benefit and how the music exercise from Meludia is connected to the selected speech exercise, along with how the specific music exercise promotes speech understanding. The last column provides further explanations and examples.

We asked Teresa Schneider if she would recommend Meludia to other speech therapists, and she responded:

“Yes, definitely. I see Meludia as an extremely effective—and at the same time low-threshold—tool for promoting auditory skills at the nonverbal level. Therapists should familiarize themselves with Meludia’s content and exercise categories beforehand. This way, they can select exercises that are specifically suited to the individual. It is crucial that the musical tasks are not isolated but embedded in linguistically relevant contexts and supplemented by language transfer tasks. The table provides a helpful overview of which Meludia exercises are suitable for which speech therapy goals, for example, differentiating similar-sounding sounds.

“It is important to emphasize that Meludia is by no means a substitute for real-life hearing and language experiences. Children need to understand the world in the truest sense of the word. Language is learned in everyday life—through concrete situations, social interaction, and multisensory experiences. Exclusively digital hearing training does not lead to success.

“We therefore view Meludia as a therapeutic supplement, not as the primary tool. It can be used specifically to promote individual auditory skills and, at the same time, serves as a motivator, as children often perceive the exercises as a game. Precisely because many children spend a lot of time with digital media anyway, its deliberate and targeted use in a therapeutic setting is even more important.”

When used in this way, Meludia can serve as an objective feedback tool for cochlear implant users who have the time and motivation to train on their own between therapy sessions. With this article, the bridging exercises, and Meludia, therapists can be empowered with the tools they need to coach cochlear implant recipients who want to get the most from their implants and the benefits from music training.

“I am not musical or have ever played an instrument. With Meludia, I can gain musical skills despite my lack of previous musical knowledge or experience—and it is fun!”

A cochlear implant user who has used Meludia in speech therapy

Free Music Training With Meludia

Support cochlear implant users who would like to build their listening skills at home with Meludia—a fun and playful music training tool. myMED-EL users get 12 months of free access.* It is also possible for recipients to renew 12-month subscriptions for free at this time.

Professionals can download the entire free resource on the MED-EL Academy at:

Course: Meludia and Speech Understanding: BRIDGING EXERCISES

In addition to the course, hearing professionals can view our ExpertsONLINE video on this topic for more details.

Special thanks to Teresa Schneider, Speech Therapist and Head of Therapy at the LZH in Dornbirn, Austria and MED-EL, for allowing us to interview her for this article and contributing to the development of the new MED-EL rehabilitation resource, Meludia and Speech Understanding: Bridging Exercises.

* Offer may not be valid in all countries, such as Japan, due to local laws and restrictions. Children 4 and 5 years of age may benefit from Meludia with the help of an adult.

References

-

[1]

Boyer, J., & Stohl, J. (2022). MELUDIA – Online music training for cochlear implant users. Cochlear Implants International, 23(5), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2022.2069313

-

[2]

Calvino, M., Zuazua, A., Sanchez-Cuadrado, I., Gavilán, J., Mancheño, M., Arroyo, H., & Lassaletta, L. (2024). Meludia platform as a tool to evaluate music perception in pediatric and adult cochlear implant users. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 281(2), 629–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-08121-7

-

[3]

Frosolini, A., Franz, L., Badin, G., Mancuso, A., Filippis, C. de, & Marioni, G. (2024). Quality of life improvement in Cochlear implant outpatients: a non-randomized clinical trial of an auditory music training program. International Journal of Audiology, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2024.2428421

-

[4]

Fujioka, T., Ross, B., Kakigi, R., Pantev, C., & Trainor, L. J. (2006). One year of musical training affects development of auditory cortical-evoked fields in young children. Brain, 129(10), 2593–2608. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl247

-

[5]

Ho, Y.-C., Cheung, M.-C., & Chan, A. S. (2003). Music Training Improves Verbal but Not Visual Memory: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Explorations in Children. Neuropsychology, 17(3), 439–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.17.3.439

-

[6]

Jiam, N. T., Deroche, M. L., Jiradejvong, P., & Limb, C. J. (2019). A Randomized Controlled Crossover Study of the Impact of Online Music Training on Pitch and Timbre Perception in Cochlear Implant Users. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 20(3), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-018-00704-0

-

[7]

Kraus, N., Slater, J., Thompson, E. C., Hornickel, J., Strait, D. L., Nicol, T., & White-Schwoch, T. (2014). Music Enrichment Programs Improve the Neural Encoding of Speech in At-Risk Children. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(36), 11913–11918. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1881-14.2014

-

[8]

Moreno, S., Marques, C., Santos, A., Santos, M., Castro, S. L., & Besson, M. (2009). Musical Training Influences Linguistic Abilities in 8-Year-Old Children: More Evidence for Brain Plasticity. Cerebral Cortex, 19(3), 712–723. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn120

-

[9]

Nardo, W. D., Schinaia, L., Anzivino, R., Corso, E. D., Ciacciarelli, A., & Paludetti, G. (2015). Musical training software for children with cochlear implants. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica: Organo Ufficiale Della Societa Italiana Di Otorinolaringologia e Chirurgia Cervico-Facciale, 35(4), 249–257. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4731893/

-

[10]

Schlaug, G., NORTON, A., OVERY, K., & WINNER, E. (2005). Effects of Music Training on the Child’s Brain and Cognitive Development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1060(1), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1360.015

-

[11]

Slater, J., Skoe, E., Strait, D. L., O’Connell, S., Thompson, E., & Kraus, N. (2015). Music training improves speech-in-noise perception: Longitudinal evidence from a community-based music program. Behavioural Brain Research, 291, 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2015.05.026

-

[12]

Smith, L., Bartel, L., Joglekar, S., & Chen, J. (2017). Musical Rehabilitation in Adult Cochlear Implant Recipients With a Self-administered Software. Otology & Neurotology, 38(8), e262–e267. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000001447

-

[13]

Strait, D. L., & Kraus, N. (2011). Can You Hear Me Now? Musical Training Shapes Functional Brain Networks for Selective Auditory Attention and Hearing Speech in Noise. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 113. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00113

-

[14]

Torppa, R., Faulkner, A., Huotilainen, M., Järvikivi, J., Lipsanen, J., Laasonen, M., & Vainio, M. (2014). The perception of prosody and associated auditory cues in early-implanted children: The role of auditory working memory and musical activities. International Journal of Audiology, 53(3), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.872302

References

Johanna Boyer

Johanna Boyer, M.A., has worked as a musicologist with MED-EL since 2012, where she focuses on music, and cochlear implants (CIs). A leading expert in this field, her work explores how people experience and perceive music through cochlear implants. As a result, Johanna has been at the forefront of new industry standards, innovative projects that connect music, people, and hearing implants. She has contributed to shaping how hearing implants process music and the role music plays in hearing rehabilitation. Johanna’s mission is to help CI users get the most from their devices. She has authored the Musical EARS handbook (a collection of musical activities to support the auditory rehabilitation of children with cochlear implants), researched the suitability of the Meludia music training software for CI recipients, and co-directed the MED-EL Sound Sensation Music Festival. Johanna holds a M.A. degree in musicology with minors in music education and sociology from the University of Würzburg, Germany.

Nathan Schackow, MA

Nathan is part of the MED-EL Professionals Blog editorial team. With a background as an English lecturer, Nathan has specialized in writing about innovations in hearing technology and care since 2020. His passion lies in translating complex science into clear, accessible communication that helps inform, inspire, and improve lives.

Was this article helpful?

Thanks for your feedback.

Sign up for newsletter below for more.

Thanks for your feedback.

Please leave your message below.

CTA Form Success Message

Send us a message

Field is required

John Doe

Field is required

name@mail.com

Field is required

What do you think?

The content on this website is for general informational purposes only and should not be taken as medical advice. Please contact your doctor or hearing specialist to learn what type of hearing solution is suitable for your specific needs. Not all products, features, or indications shown are approved in all countries.

Johanna Boyer

Johanna Boyer, M.A., has worked as a musicologist with MED-EL since 2012, where she focuses on music, and cochlear implants (CIs). A leading expert in this field, her work explores how people experience and perceive music through cochlear implants. As a result, Johanna has been at the forefront of new industry standards, innovative projects that connect music, people, and hearing implants. She has contributed to shaping how hearing implants process music and the role music plays in hearing rehabilitation. Johanna’s mission is to help CI users get the most from their devices. She has authored the Musical EARS handbook (a collection of musical activities to support the auditory rehabilitation of children with cochlear implants), researched the suitability of the Meludia music training software for CI recipients, and co-directed the MED-EL Sound Sensation Music Festival. Johanna holds a M.A. degree in musicology with minors in music education and sociology from the University of Würzburg, Germany.

Nathan Schackow, MA

Nathan is part of the MED-EL Professionals Blog editorial team. With a background as an English lecturer, Nathan has specialized in writing about innovations in hearing technology and care since 2020. His passion lies in translating complex science into clear, accessible communication that helps inform, inspire, and improve lives.