MED-EL

Published Aug 01, 2018

Creating an Electrode Lead Channel for Impact Protection: Dr. Peter Roland

When it comes to cochlear implant reliability, we’re continuously striving to deliver the most reliable implants possible. We don’t do this for a number on paper or a colorful chart—our goal is to deliver the best possible outcomes for every one of our recipients. We’re proud that our cochlear implants offer outstanding long-term reliability and outstanding hearing outcomes.

However, to help ensure the best patient outcomes possible, it is essential to follow proper surgical techniques—including creating an electrode lead channel during implantation. This bony channel is a highly effective way to protect the electrode lead from external impacts.

Today, Dr. Peter Roland will explain why he went back to drilling a bony channel for the electrode lead. Dr. Roland is an Emeritus Professor & Chairman of the Department of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Dr. Roland is also surgical consultant & instructor at the MED-EL Surgical Academy. For complete surgical guidelines with all of our implants, please refer to the official MED-EL surgical guidelines.

Let’s go over to Dr. Roland.

Evolving Surgical Techniques: My Experience

Over the years, I followed the lead of other high-volume cochlear implant surgeons and became quite comfortable using a tight subperiosteal pocket to immobilize the implanted stimulator receiver, even though a recessed bed is recommended by the manufacture’s labeling.

Labeling, after all, is based on the technique used for the original pivotal clinical trials required for FDA approval. Surgical techniques advance, and yet the labeling often cannot be changed without additional clinical trials, which can be a rigorous process that takes several years and costs a lot money.

Provided the subperiosteal pocket is truly “tight” (which requires considerable care and that something is done to prevent anterior displacement, such as a low “ledge” of bone, suturing the periosteum to bone), I remain very confident that the subperiosteal pocket approach is reliable for most situations.

Previously, I had thought that the same reasoning applied to the recommendation to drill a bony channel for the electrode lead. At that time, I believed that the recommended electrode lead channel, like the bed for the stimulator receiver, was unnecessary and I stopped making a channel for the electrode lead.

Then I saw bench data on electrode lead wire fractures, which strongly suggested my assumption was wrong. The titanium receiver housing is robust and can withstand direct impact. However, the ultra-thin wires of the electrode array can be damaged by a direct impact if left unprotected. Wire fractures can occur as a result of impact trauma with all available electrodes. After seeing the product testing data, I changed back to fully recessing the electrode lead in a bony channel. With a proper electrode lead channel, the risk of impact wire fractures can be very effectively reduced. It doesn’t take long, and it gives me confidence that I have done all that I can to minimize the need for a revision operation secondary to impact wire fractures.

Ideally, the electrode lead should be fully recessed so that the most superficial portion of the lead lies deep to the surface of the cortical bone, as is suggested in the surgical manual.

Ideally, the electrode lead should be fully recessed so that the most superficial portion of the lead lies deep to the surface of the cortical bone, as is suggested in the surgical manual.

Creating an Electrode Lead Channel

Once you have decided where you wish to place the stimulator-receiver, simply use a 3 or 4 mm burr to create a channel from the stimulator receiver to the mastoid cavity. At best, the entire electrode lead is fully beneath the surface of the bone from the point at which the electrode passes out of the stimulator-receiver overmold until it enters the mastoid cavity.

If the bone is too thin to entirely recess the electrode lead, the data clearly indicates that even a partially recessed electrode lead receives significant protection.

Can’t See This Video?

Having problems viewing this video? Watch it on YouTube.

The channel should slope medially as it enters the mastoid and the transition into the mastoid cavity should be smooth, without any sharp edges.

The “rebound” tension in the electrode lead and movement associated with closing can displace the electrode lead from the channel. So, during wound closure one must take care to ensure that the electrode lead remains in the channel and that the coiled portion remains within the mastoid.

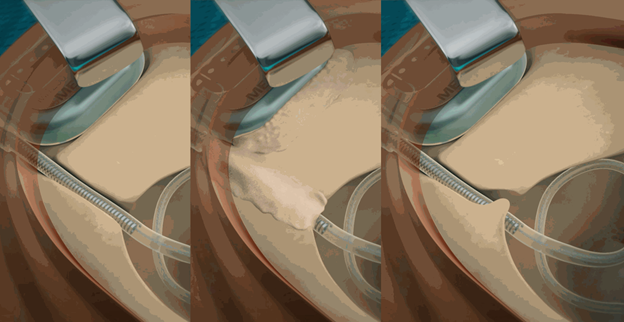

Three methods of securing the lead: The first shows a tight channel anteriorly as the lead passes into the mastoid, the second illustrates the use of either Gelfoam, fascia, or bone pate to secure the lead and immobilize it. The third method demonstrates a “kink” in the mastoid end of the channel with a partial bridge of bone to retain and fix the lead.

The coiled lead can be retained within the mastoid cavity by making sure the lead is tucked firmly under the over-hanging edges of the cavity. A postage stamp sized piece of Gelfoam can be used to temporarily close the cavity and prevent displacement of the coil.

Moreover, keeping the lead in firm contact with the bone at the bottom of the channel should help prevent the electrode from being lifted out of the channel by later bony regrowth. Several methods can be used to accomplish this task:

- Using a tight form-fit channel, anteriorly locking the electrode in the channel

- Bone wax, Gelfoam, strips of fascia, bone pate, or bone cement can be used to cover the channel. This is intended to keep the lead pressed into the bottom of the channel and prevent movement.

- Drilling a slight undercut of the surface bone, or creating a slight “kink” in the mastoid end of the channel to hold the lead in place (sometimes called a “partial bridge” technique).

I like to use a piece of Gelfoam, but any of these methods are an effective way to fix the electrode within the bony channel.

I think what’s most important to remember is that drilling a channel only takes a minute or so—and if it prevents even one patient from needing a revision operation because of wire fractures, I believe the time is well spent.

Thanks Dr. Roland!

Want to see detailed HD surgical video demonstrating how to create an electrode channel? Check out this great surgical case study from Prof. Paul Van de Heyning, or this excellent bilateral case with Prof. Lorne Parnes.

*Not all products, indications, and features shown are available in all areas. Please contact your local MED-EL representative for more information.

MED-EL

Was this article helpful?

Thanks for your feedback.

Sign up for newsletter below for more.

Thanks for your feedback.

Please leave your message below.

CTA Form Success Message

Send us a message

Field is required

John Doe

Field is required

name@mail.com

Field is required

What do you think?

The content on this website is for general informational purposes only and should not be taken as medical advice. Please contact your doctor or hearing specialist to learn what type of hearing solution is suitable for your specific needs. Not all products, features, or indications shown are approved in all countries.

MED-EL