MED-EL

Published Jan 21, 2021

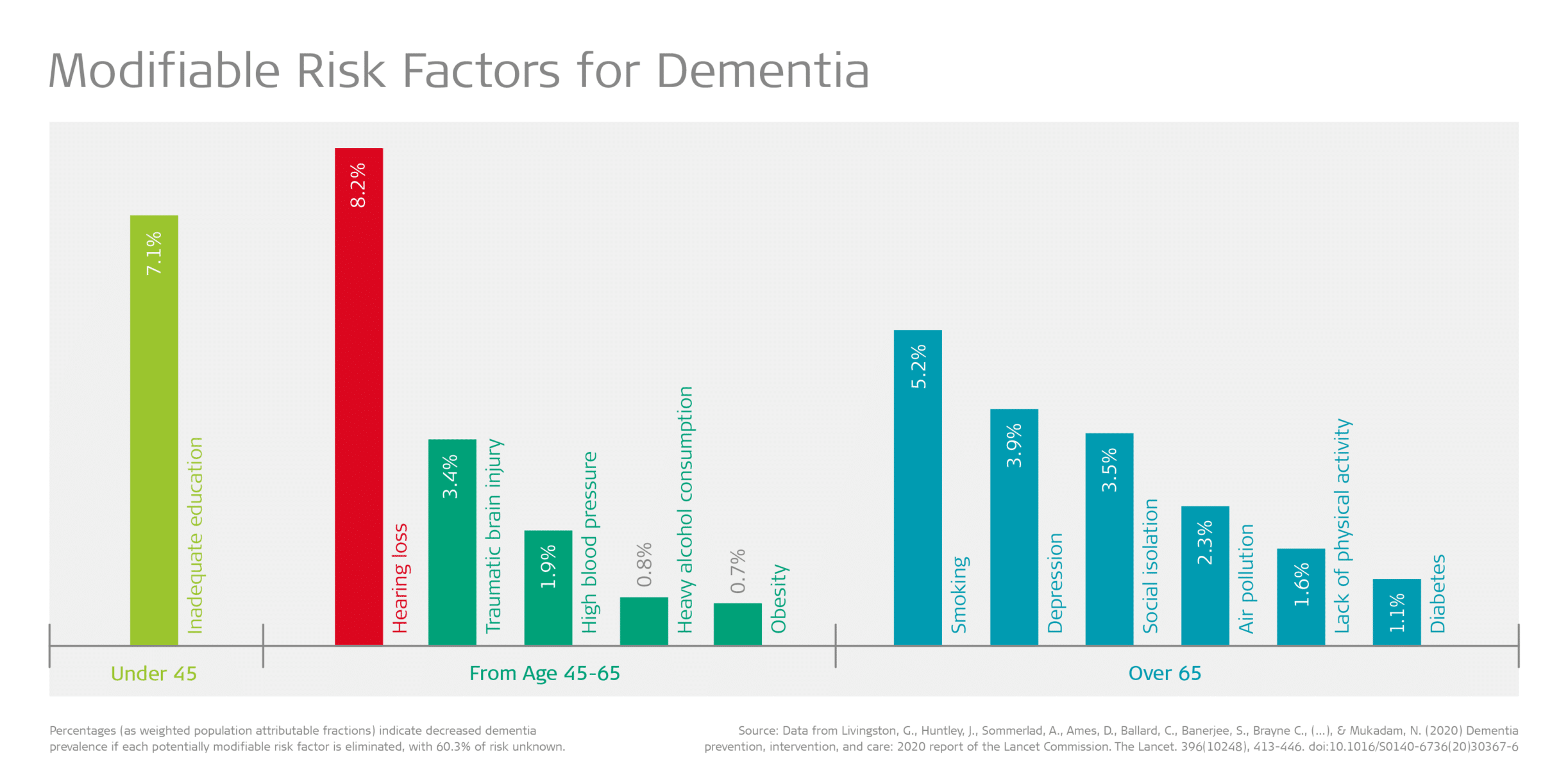

Hearing Loss is the Number One Modifiable Risk Factor for Dementia

With the global population of 7.8 billion expected to reach 9.9 billion by 2050,[1] the challenges for healthcare systems are well documented.[2] However, as the population ages this adds a further layer of complexity. The United Nations note that in the next 30 years the percentage of adults over 60 will rise to 21.4% from just 13.5% at present.[3] In fact, the number of people over 70 years will double over the same period.

This brings into sharp focus the impact of age-related disease burdens, including hearing loss and dementia.

Hearing Loss and Dementia

One in four people believe that nothing can be done to prevent dementia[4] despite a growing body of evidence that recognizes the elimination of 12 potentially modifiable risk factors which could prevent or delay up to 40% of dementia cases.[5] Importantly, the primary modifiable risk factor is hearing loss in midlife, which reduces risk by 8%.[6] This is followed by depression (4%) and isolation in later life (4%), both of which frequently accompany hearing loss.

The WHO estimates that 466 million people worldwide, or 5% of the population, are living with a disabling hearing loss, and this figure is expected to almost double to 900 million people by 2050.[7] The data for those living with dementia are equally as stark – globally 50 million people are living with the disease, at a cost of US$ 818 billion. The number of people affected is expected to triple by 2050.[8] These rapid increases are a clear and early warning.

Since as early as the 1980s, studies have indicated an association between cognitive impairment and a decline in sensory acuity. Such early work has been followed by decades of ongoing research that has sought to specifically explore hearing loss and poorer cognitive outcomes. [9] [10]

It is now widely accepted that untreated hearing loss leads to structural and functional atrophy within the brain as a result of deprived auditory stimulation and an increase in the cognitive load required to process environmental sounds, speech and music. [11] [12] [13] A recent study on a large population in the US (n=347)[14] concluded that for every 10 dB of hearing loss, the rate of cognitive decline increased. Those living with untreated hearing loss experienced an accelerated rate by as much as 30-40% compared to their peers with normal hearing.

The World Health Organization identifies being able to contribute to society and relationship development as two of the five functional abilities that contribute to healthy aging.[15] Yet multiple papers[16] [17] report hearing loss as a barrier to these crucial functional abilities, and a correlation between hearing loss and both fragmented communication and diminished social engagement has been observed. Limited social networks, often associated with withdrawal, isolation and loneliness, are shown to increase the risk of dementia by as much as 60%.[18]

Hearing Loss Intervention

Despite hearing loss being the third most prevalent chronic health condition for adults[19] and the proven links to cognitive decline, isolation, depression, and increased health and social care needs, our research shows that adults with hearing loss may not seek treatment for almost a decade.

Adults living with severe-to-profound hearing loss who use cochlear implants were found to have improved cognitive outcomes that were statistically significant for measures including reaction time, cognitive flexibility, paired-associate learning, and working memory when compared to those waiting to receive a cochlear implant. [20] It is believed that the outcomes are supported by a reduction in cognitive load, along with increased brain stimulation[21] as people reengage in verbal communication across social connections or working environments. Additional outcomes related to improved cognitive function and quality of life, as well as a reduced depression, have also been reported.[22]

Support Needed for Reform and Research

Existing research is insufficient to establish a causal relationship between hearing loss and cognitive decline, and more studies that address this question need to be undertaken. Larger longitudinal studies may hold the key to furthering our understanding of the correlation between these important topics. However, the extensive evidence to date, of which just a small sample has been shared here, suggests that a relationship between the two exists.

Given the proven human and economic impacts of hearing loss and cognitive decline, we advocate for an increase in ongoing research alongside national policy reforms for a holistic life-course approach focused on hearing loss identification, prevention and intervention for people of all ages.

We support the Hearing Health Forum EU’s hearing health policy frameworks for adults, and the recommendations of leading authorities, including the Lancet Commission and the World Health Organization, in transforming healthcare services for those living with dementia and hearing loss.

Subscribe to Stay Informed

Don’t miss future updates like this one from our MED-EL Professionals Blog—subscribe now!

References

[1] Population Reference Bureau. (2020). World Population Data Sheet. Retrieved November 26, 2020, from https://www.prb.org/2020-world-population-data-sheet/

[2] D’Haese, P.S.C., Van Rompaey, V., De Bodt, M,. & Van de Heyning, P. (2019). Severe Hearing Loss in the Aging Population Poses a Global Public Health Challenge. How Can We Better Realize the Benefits of Cochlear Implantation to Mitigate This Crisis? Front Public Health. 7, 227. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00227

[3] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2019). World Population Prospects 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2020, from https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/

[4] Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2019). World Alzheimer’s Report 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2020, from https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2019/

[5] Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Brayne C., (…), & Mukadam, N. (2020) Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 396(10248), 413-446. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

[6] Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Brayne C., (…), & Mukadam, N. (2020) Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 396(10248), 413-446. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

[7] World Health Organization. (2020). Deafness and Hearing Loss. Retrieved November 26, 2020, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/hearing-loss#tab=tab_2

[8] Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2019). Dementia Facts & Figures. Retrieved November 26, 2020, from https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/

[9] Taljaard, D. S., Olaithe, M., Brennan-Jones, C. G., Eikelboom, R. H., & Bucks, R. S. (2016). The relationship between hearing impairment and cognitive function: a meta-analysis in adults. Clin. Otolaryngol. 41, 718–729. doi:10.1111/ coa.12607

[10] Sarant, J., Harris, D., Busby, P., Maruff, P., Schembri, A., Dowell, R., & Briggs, R. (2019). The Effect of Cochlear Implants on Cognitive Function in Older Adults: Initial Baseline and 18-Month Follow Up Results for a Prospective International Longitudinal Study. Front Neurosci. 13, 789. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00789

[11] Fulton, S. E., Lister, J. J., Bush, A. L. H., Edwards, J. D., & Andel, R. (2015). Mechanisms of the hearing–cognition relationship. Semin. Hear. 36, 140–149. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1555117

[12] Peelle, J. E., Wingfield, A. (2016). The neural consequences of age-related hearing loss. Trends Neurosci. 39, 486–497. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2016.05.001

[13] Eckert, M. A., Cute, S. L., Vaden, K. I., Jr, Kuchinsky, S. E., & Dubno, J. R. (2012). Auditory cortex signs of age-related hearing loss. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. 13(5), 703–713. doi:10.1007/s10162-012-0332-5

[14] Lin, F. R., Ferrucci, L., Metter, E. J., An, Y., Zonderman, A. B., & Resnick, S. M. (2011). Hearing loss and cognition in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neuropsychology. 25, 763–770. doi:10.1037/a0024238

[15] World Health Organization. (2020). ‘Ageing: Healthy ageing and functional ability’. Retrieved November 26, 2020, from https://www.who.int/westernpacific/news/q-a-detail/ageing-healthy-ageing-and-functional-ability. Accessed 26 November 2020

[16] Contrera, K.J., Sung, Y.K., Betz, J., Li, L., & Lin, F.R. Change in loneliness after intervention with cochlear implants or hearing aids. Laryngoscope. 2017 Aug;127(8):1885-1889. doi:10.1002/lary.26424

[17] Shukla, A., Harper, M., Pedersen, E., (…), &Reed, N.S. Hearing Loss, Loneliness, and Social Isolation: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020, March. doi:10.1177/0194599820910377

[18] Barnes, L. L., Mendes De Leon, C. F., Wilson, R. S., Bienias, J. L., & Evans, D. A. (2004). Social resources and cognitive decline in a population of older African Americans and whites. Neurology. 63, 2322–2326. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000147473.04043.b3

[19] Masterson, E.A., Bushnell, P.T., Themann, C.L., &Morata, T.C. (2016). Hearing Impairment Among Noise-Exposed Workers — United States, 2003–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 65:389–394. doi:10.3390/ijerph15102120

[20] Jayakody, D.M.P., Friedland, P.L., Nel, E., Martins, R.N., Atlas, M.D., & Sohrabi, H.R. (2017). Impact of Cochlear Implantation on Cognitive Functions of Older Adults: Pilot Test Results.Otol Neurotol. 38(8), 89-295.

[21] Fulton, S. E., Lister, J. J., Bush, A. L. H., Edwards, J. D., & Andel, R. (2015). Mechanisms of the hearing–cognition relationship. Semin. Hear. 36, 140–149. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1555117

[22] Mosnier, I., Bebear, J., Marx, M., Fraysse, B., Truy, E., Lina-Granade, G., (…), & Sterkers, O. (2015). Improvement of cognitive function after cochlear implantation in elderly patients. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 141, 442–450. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.129

MED-EL

Was this article helpful?

Thanks for your feedback.

Sign up for newsletter below for more.

Thanks for your feedback.

Please leave your message below.

CTA Form Success Message

Send us a message

Field is required

John Doe

Field is required

name@mail.com

Field is required

What do you think?

MED-EL