Published Dec 04, 2025

FDA Expands MED-EL Criteria to Revolutionize Candidacy

On November 26, 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved new indications for MED-EL cochlear implants in children, providing the broadest candidacy criteria available. This approval offers unprecedented access for many children who would have previously been denied a cochlear implant (CI).

The FDA first approved cochlear implantation for children in 1990. Pediatric CI indications changed little over the next 30 years. By the time indications expanded to include children aged ≥ 9 months, research and professionals agreed that the change was not enough.[1–9]

The American Academy of Pediatrics and Early Hearing Detection and Identification guidelines recommend “timely and appropriate intervention before 6 months of age,”[10] and the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing recommends appropriate intervention by 3 months of age.[11]

Why is this approval important?

Undeniable evidence on the importance of early access to sound is nothing new, but we continue to study the impacts of hearing on critical periods of neurocognitive development. While the critical period for speech perception extends beyond 1 year of age, “the critical period for language development is within the first year of life.”[12] As such, research on language development and developmental trajectories show greater benefit in children implanted under 9 months of age compared to those implanted at ages ≥ 9 months.[1–6] According to Kral et al., restoring hearing before 9 months of age is also likely key to critical periods of neural development, including multimodal interactions and brain connectivity.[9]

Auditory deprivation in early childhood affects far more than speech and language skills. In addition to language development, research shows that “children are highly dependent on hearing” for psychosocial skills, neurocognitive maturity, learning, literacy, academic success, and quality of life.[13] These critical life skills continue to develop well into elementary age. Thus, expanded indications must consider more than lower ages at implantation and children born with profound hearing loss. In 2015, Carlson et al. argued that children with varying degrees of residual hearing who continue to struggle with hearing aids “are the very group that would likely perform best” and “may miss a critical window of cortical plasticity.” These children must not be overlooked or forgotten.

Unlike adults with residual hearing, the primary goal of implanting children is developmental, including age-appropriate language skills and neurocognitive milestones. Studies show that children need better audibility, bandwidth, and signal-to-noise ratios than adults for age-appropriate speech understanding.[14] Research shows that children need an aided Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) of ≥ 0.65, indicating that at least 65% of speech is audible with hearing aids.[15] However, previous CI indications required children under 18 years of age to score 30% or worse on speech understanding with hearing aids.

Studies comparing CI outcomes to performance with hearing aids suggest that children with severe to profound and steeply-sloping hearing loss using CIs have better speech perception scores than children using hearing aids.[16–24] Research also shows that children with preoperative residual hearing benefit from CIs with and without hearing preservation.[25–28] Park et al. found “that delay of cochlear implantation, even for children with significant levels of residual hearing, leads to poorer outcomes.” Thus, delaying implantation in children who continue to struggle with hearing aids may do more harm than good.

What are the new candidacy criteria for MED-EL cochlear implants in children?

Table 1 shows the latest FDA-approved indications for children with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL).

Table 1. FDA-Approved Pediatric CI Indications for Bilateral SNHL by Manufacturer

Note. CNC = Consonant-Nucleus-Consonant; MAIS = Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale; ESP = Early Speech Perception Test; IT-MAIS = Infant-Toddler Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale; MLNT = Mutlisyllabic Lexical Neighborhood Test; PBK = Phonetically-Balanced Kindergarten Test; HINT-C = Hearing-in-Noise Test for Children. MED-EL labeling defines profound SNHL as an unaided, three-frequency pure-tone average (PTA3) ≥ 90 dB HL at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz. Moderately-severe to profound SNHL is defined by a PTA3 ≥ 55 dB HL at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz and unaided thresholds ≥ 70 dB HL at 2-8 kHz. Moderate to profound SNHL for individuals aged ≥ 6 years is defined by a low-frequency pure-tone average (LFPTA) > 40 dB HL at 250, 500, and 1000 Hz and unaided thresholds ≥ 65 dB HL at 3-8 kHz.

How did MED-EL study expand CI indications in children?

MED-EL conducted an FDA clinical trial to evaluate outcomes in children aged 7-71 months who did not meet traditional candidacy criteria. The study included two groups:

- Group 1: 38 children implanted at five CI centers between 7 and 71 months of age. These children enrolled in the study before cochlear implant surgery and returned for study visits throughout the first year of device use.

- Group 2: 209 children implanted at seven CI centers between 3 and 71 months of age. This group involved analysis of medical records for children who had already used a MED-EL cochlear implant for at least 1 year.

The goal was to measure clinical success rates on speech recognition and auditory skill development through 12 months after activation. Performance with the cochlear implant was compared to preimplant scores with hearing aids using recognized tests like MLNT and the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire.

Key Findings:

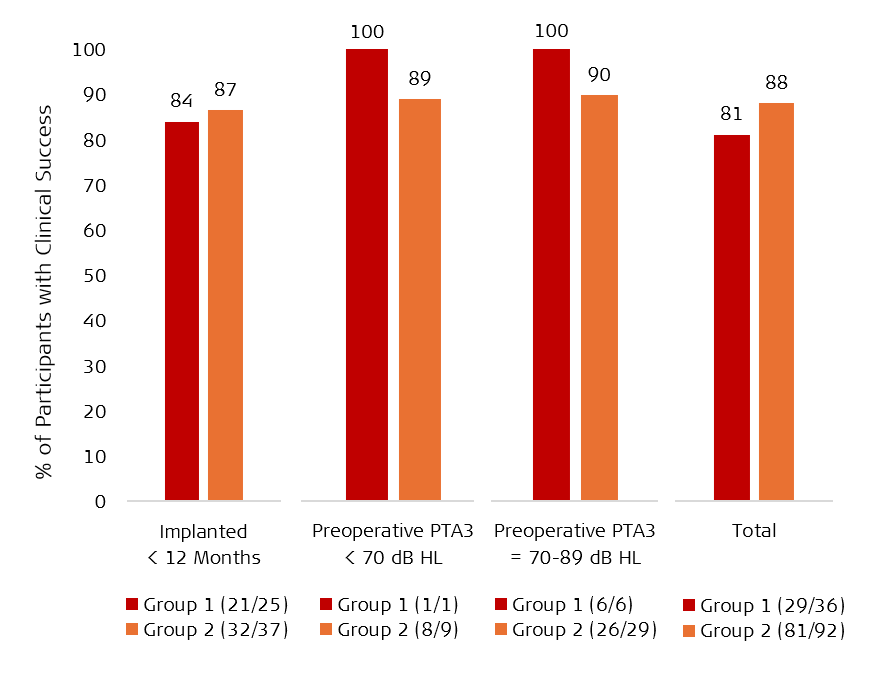

- Group 1: 81% achieved clinical success within the first year.

- Group 2: 88% achieved clinical success, a statistically significant result (p = .002).

- Many children implanted before 12 months showed auditory skills similar to children with normal hearing by 1 year after activation, supporting earlier implantation.

- Children implanted at 12 months and older with residual hearing also showed high success rates.

- The rate of major complications was low in both study groups. All complications were known risks of cochlear implantation, and children implanted under 12 months did not have more complications than other children.

Figure 1 shows high success rates in both study groups for children implanted under 12 months old and children aged 12-71 months with residual hearing.

Figure 1. Clinical success rates in both study groups and key subgroups.

Note. PTA3 = three-frequency pure-tone average (average of unaided hearing thresholds at 500, 1000, and 2000 hertz [Hz]), dB HL = decibels in hearing level (a measure of loudness used for hearing tests and audiograms). A PTA3 less than 70 dB HL is better than severe hearing loss. A PTA3 of 70-89 dB HL is severe hearing loss but better than profound SNHL.

What does it all mean?

This data shows MED-EL cochlear implants are safe and effective for children implanted between 7 and 71 months with bilateral SNHL and leads to high success rates in speech recognition and auditory skill development. Over 80% of children achieved clinical success within the first year of implant use, and the retrospective group showed a significant success rate of 88% (95% CI [80, 94], p = .002). Study results paved the way for FDA approval of expanded indications. MED-EL’s new candidacy criteria align with the Cochlear Implant: Patient Access To Hearing (CI:PATH) initiative, which promotes timely referrals and evidence-based guidelines so every family can make informed decisions about cochlear implants.[29]

To learn more about our exciting new expanded indications, you can read the official press release here.

References

- Colletti, L. (2009). Long-term follow-up of infants (4–11 months) fitted with cochlear implants. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 129(4), 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480802495453

- Chweya, C. M., May, M. M., DeJong, M. D., Baas, B. S., Lohse, C. M., Driscoll, C. L. W., & Carlson, M. L. (2021). Language and Audiological Outcomes Among Infants Implanted Before 9 and 12 Months of Age Versus Older Children: A Continuum of Benefit Associated With Cochlear Implantation at Successively Younger Ages. Otology & Neurotology, 42(5), 686–693. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000003011

- Dettman, S., Choo, D., Au, A., Luu, A., & Dowell, R. (2021). Speech Perception and Language Outcomes for Infants Receiving Cochlear Implants Before or After 9 Months of Age: Use of Category-Based Aggregation of Data in an Unselected Pediatric Cohort. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(3), 1023–1039. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_jslhr-20-00228

- Culbertson, S. R., Dillon, M. T., Richter, M. E., Brown, K. D., Anderson, M. R., Hancock, S. L., & Park, L. R. (2022). Younger Age at Cochlear Implant Activation Results in Improved Auditory Skill Development for Children With Congenital Deafness. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65(9), 3539–3547. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_jslhr-22-00039

- Cottrell, J., Spitzer, E., Friedmann, D., Jethanamest, D., McMenomey, S., Roland, J. T., & Waltzman, S. (2024). Cochlear Implantation in Children Under 9 Months of Age: Safety and Efficacy. Otology & Neurotology, 45(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000004071

- Karltorp, E., Eklöf, M., Östlund, E., Asp, F., Tideholm, B., & Löfkvist, U. (2020). Cochlear implants before 9 months of age led to more natural spoken language development without increased surgical risks. Acta Paediatrica, 109(2), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14954

- Carlson, M. L., Sladen, D. P., Haynes, D. S., Driscoll, C. L., DeJong, M. D., Erickson, H. C., Sunderhaus, L. W., Hedley-Williams, A., Rosenzweig, E. A., Davis, T. J., & Gifford, R. H. (2015). Evidence for the Expansion of Pediatric Cochlear Implant Candidacy. Otology & Neurotology, 36(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000000607

- Park, L. R., Gagnon, E. B., & Brown, K. D. (2021). The Limitations of FDA Criteria: Inconsistencies with Clinical Practice, Findings, and Adult Criteria as a Barrier to Pediatric Implantation. Seminars in Hearing, 42(04), 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1739370

- Kral, A., Kishon-Rabin, L., O’Donoghue, G. M., & Romeo, R. R. (2025). Sensorimotor contingencies in congenital hearing loss: The critical first nine months. Hearing Research, 467, 109401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2025.109401

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (n.d.) Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Frequently Asked Question (FAQ) Guide for Pediatricians. Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Frequently Asked Question (FAQ) Guide for Pediatricians. Retrieved November 14, 2025, from https://www.infanthearing.org/coordinator_toolkit/section8/EDHI_FAQ11.pdf

- Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. (2007). Year 2019 Position Statement: Principles and Guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programs. Pediatrics, 120(4), 898–921. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2333

- Leigh, J., Dettman, S., Dowell, R., & Briggs, R. (2013). Communication Development in Children Who Receive a Cochlear Implant by 12 Months of Age. Otology & Neurotology, 34(3), 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0b013e3182814d2c

- Gifford, R. H. (2016). Expansion of Pediatric Cochlear Implant Indications. The Hearing Journal, 69(12), 8–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.hj.0000511125.71672.3e

- Leal, C., Marriage, J., & Vickers, D. (2016). Evaluating recommended audiometric changes to candidacy using the speech intelligibility index. Cochlear Implants International, 17(sup1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2016.1151635

- Leal, C., Marriage, J., & Vickers, D. (2016). Evaluating recommended audiometric changes to candidacy using the speech intelligibility index. Cochlear Implants International, 17(sup1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2016.1151635

- Yoshinaga-Itano, C., Baca, R. L., & Sedey, A. L. (2010). Describing the Trajectory of Language Development in the Presence of Severe-to-Profound Hearing Loss. Otology & Neurotology, 31(8), 1268–1274. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0b013e3181f1ce07

- Gratacap, M., Thierry, B., Rouillon, I., Marlin, S., Garabedian, N., & Loundon, N. (2015). Pediatric Cochlear Implantation in Residual Hearing Candidates. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489414566121

- Wilson, K., Ambler, M., Hanvey, K., Jenkins, M., Jiang, D., Maggs, J., & Tzifa, K. (2016). Cochlear implant assessment and candidacy for children with partial hearing. Cochlear Implants International, 17(sup1), 66–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/14670100.2016.1152014

- Park, L. R., Richter, M. E., Gagnon, E. B., Culbertson, S. R., Henderson, L. W., & Dillon, M. T. (2025). Benefits of Cochlear Implantation and Hearing Preservation for Children With Preoperative Functional Hearing: A Prospective Clinical Trial. Ear & Hearing. https://doi.org/10.1097/aud.0000000000001636

- Leigh, J. R., Dettman, S. J., & Dowell, R. C. (2016). Evidence-based guidelines for recommending cochlear implantation for young children: Audiological criteria and optimizing age at implantation. International Journal of Audiology, 55(sup2), S9–S18. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2016.1157268

- Kuthubutheen, J., Hedne, C. N., Krishnaswamy, J., & Rajan, G. P. (2012). A Case Series of Paediatric Hearing Preservation Cochlear Implantation: A New Treatment Modality for Children with Drug-Induced or Congenital Partial Deafness. Audiology and Neurotology, 17(5), 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1159/000339350

- Skarzynski, H., & Lorens, A. (2009). Electric Acoustic Stimulation in Children. Advances in Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 67, 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1159/000262605

- Wolfe, J., Neumann, S., Schafer, E., Marsh, M., Wood, M., & Baker, R. S. (2017). Potential Benefits of an Integrated Electric-Acoustic Sound Processor with Children: A Preliminary Report. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 28(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.15133

- Skarzynski, H., Lorens, A., Piotrowska, A., & Anderson, I. (2007). Partial deafness cochlear implantation in children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 71(9), 1407–1413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.05.014

- Na, E., Toupin-April, K., Olds, J., Chen, J., & Fitzpatrick, E. M. (2024). Benefits and risks related to cochlear implantation for children with residual hearing: a systematic review. International Journal of Audiology, 63(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2022.2155879

- Na, E., Toupin-April, K., Olds, J., Whittingham, J., & Fitzpatrick, E. M. (2022). Clinical characteristics and outcomes of children with cochlear implants who had preoperative residual hearing. International Journal of Audiology, 61(2), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2021.1893841

- Chiossi, J. S. C., & Hyppolito, M. A. (2017). Effects of residual hearing on cochlear implant outcomes in children: A systematic-review. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 100, 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.06.036

- Schaefer, S., Sahwan, M., Metryka, A., Kluk, K., & Bruce, I. A. (2021). The benefits of preserving residual hearing following cochlear implantation: a systematic review. International Journal of Audiology, 60(8), 561–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1863484

- CI:PATH. (2025). Who we are. Cochlear Implant Patient Access to Hearing. Retrieved November 21, 2025, from https://www.cipath.org/about

References

Was this article helpful?

Thanks for your feedback.

Sign up for newsletter below for more.

Thanks for your feedback.

Please leave your message below.

Thanks for your message. We will reply as soon as possible.

Send Us a Message

Field is required

John Doe

Field is required

name@mail.com

Field is required

What do you think?

© MED-EL Medical Electronics. All rights reserved. The content on this website is for general informational purposes only and should not be taken as medical advice. Contact your doctor or hearing specialist to learn what type of hearing solution suits your specific needs. Not all products, features, or indications are approved in all countries.

.png)